| A Guy Called Gerald & Graham Massey | |

|

Attack Magazine 23rd October 2012 Link |

|

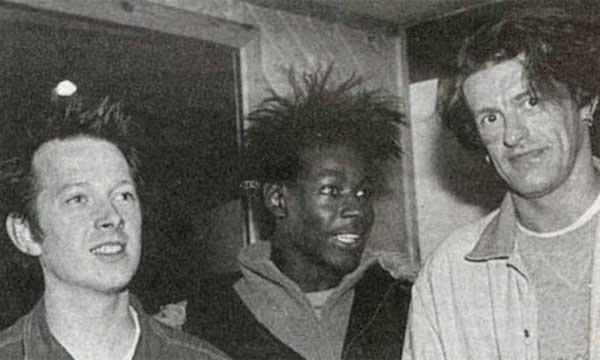

808 State’s Graham Massey and A Guy Called Gerald have reunited to perform all-analogue live acid house jams with a distinctly retro approach. When the men responsible for ‘Pacific State’ and ‘Voodoo Ray’ get together, we get excited. We chatted to the pair in advance of their performance in London this weekend to find out why the classic Manchester acid sound relied so heavily on Roland hardware and to hear Gerald’s typically forthright views on live dance music.  Back in the day: the original 808 State lineup circa 1988. (L-R: Graham Massey, Gerald Simpson, Martin Price)

Graham Massey: You have to go back to the beginning of 808 State, which was formed in 1988 by me, Gerald and a guy called Martin Price. We were doing acid house in ’88, which was quite rare in the UK at that point. John Peel used to play our first album, Newbuild, quite a lot and we started getting exposure from things like that and doing early raves and warehouse parties. Basically Aphex Twin’s label Rephlex really liked that first album and they reissued it as a triple vinyl package in about 1999. It was a bit of a lost album before they put it out again – original pressings were going for about 70 quid because I think we only pressed a thousand copies when we put it out. Then we found a load more tapes from that period and did a thing called Prebuild on Rephlex, which was a collection of acid tracks from around ’88, the early experiments – some of which were just tapes out of Gerald’s bedroom. We did a gig to launch that album but we haven’t done anything since. We just saw it as a one-off event, but since then we’ve had a lot of requests to do it again and WANG have organised another event this weekend.  Gerald and Martin in the studio, late 1980s

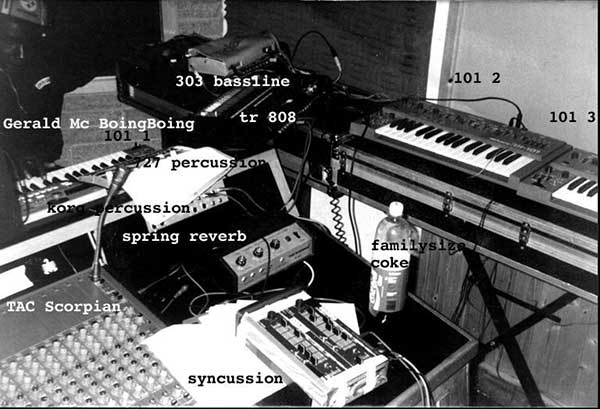

Gerald Simpson: It’s kind of like going back in time a bit but it’s gonna be enjoyable, I reckon. It’s exactly the same kind of machinery as we were using back then, really. Basically going back 25 years. What equipment are you using? Graham: It’s a lot of the old Roland gear like we used back then – the 808, the 909, the 303 and the 101 that we made records with. But, approaching it again now, I’m questioning whether to use a computer or not. Gerald: I’m totally using analogue. 303, 101, 202, 727, 909… Analogue’s kind of what the kids enjoy these days anyway. Everyone’s got a computer, so they want to see someone using the old stuff. For me it’s actually easier to use the old gear. I can do it with my eyes closed nowadays but I’ve been practising a bit with it just to make sure I’m not being overconfident. Graham: Red Bull Music Academy have loaned us a studio for three days this week so we’ll bash it out and decide what to do. It’s very last minute so it could go in different directions. That’s exciting in itself. Graham: Yeah. I mean, we’re trying to avoid doing really cliched stuff with it, but you find when you’ve got all this equipment wired together that certain tempos suit the frequencies, if you know what I mean. It’s not about having it really hard and fast. It’s about multi-layering and making almost a tapestry of things. It does dictate it’s own terms to some extent, but we like to mess with that as well. A lot of the time we’re surprising each other. It’s like, ‘Where’s he going?’ and you have to respond to things. Just seeing where it takes you… Graham: Definitely. In one sense it’s sometimes a bit scary, because the audience comes with expectations, but it’s true to the way that we first used to do acid house. You didn’t have a set list, it was very organic. It was about a process rather than a tune. Gerald: The first time we did it we got a few little new grooves together beforehand, but this time I’m thinking I might try and revisit some of the old stuff from the Newbuild album, so I’ve been programming some of that on the 303, recreating a few bits and pieces. That can be easier said than done with the 303. How good are you with programming it? Gerald: I’ve been doing it 25 years so I know how to program a tune into it. I used to write all my music with the SH-101, the 808 and the 303, so it’s not so hard to do. All you have to do is read the manual really…  Graham at BBC Manchester, 1988

Gerald: When I started out I was just using all Roland stuff because there wasn’t anything else available. People were throwing it all away so it was really cheap. At one point all I had in my studio was Roland gear. Were you trying to copy the sounds you were hearing from Chicago and Detroit? Gerald: No, it was just that they were easy to get hold of. I didn’t realise that it was the same gear they were using in Chicago until I heard a 303 on a record in about late ’86, early ’87, and I was like, ‘Oh, shit. I’ve got one of them!’ Graham: It wasn’t just about trying to emulate American music. I found the hip hop thing at the time to be very much about that. It wasn’t particularly bringing anything British to the table. Yeah, it probably took a lot longer for British hip hop to develop its own identity. That’s an interesting point because the Manchester acid, techno, warehouse scene – whatever you want to call it – soon developed a distinct sound of its own. Graham: It had a sort of UK slant to it. You can still hear that there’s a thread of UK subculture music that’s very much influenced by reggae and dub. When we were growing up in Manchester that’s what you’d always hear at parties. There was a different cultural mix in Manchester to, say, the Balearic thing that was coming out of London at the time. It reflected that sound system culture. What do you think of young producers wanting to copy the sounds from old records? Gerald: For some reason they’ve got the impression that the old school stuff sounds better somehow. I’m someone that’s progressed all the way from analogue synths through digital into samplers and then to computers. I can’t really agree with people who think the old analogue stuff automatically sounds better. One of the secrets of working with this stuff is to make your own individual sounds. I’ve been analysing some of the younger kids and I reckon there’s a few people who think all you have to do is switch on the old analogue machines and press play and you sound like you’re from the old school. I know one person who’s just spent something like eight grand and got the entire TR series and all the old Roland stuff. He reckons he got a bargain. I went round and listened and it sounds like crap. Like, ‘You’re just making a load of noises!’ It doesn’t just work like that. Back in the day – if one can say that – the people who were inspiring me were using the synths to try and make real-life sounds. It was a good exercise to learn how to shape waveforms. I get the impression that most younger producers think all you have to do is buy one of these old synths and plug it in. You’ve got to be a little bit more inventive. If you’re gonna spend all that money on something that actually isn’t really worth that much, you should do something different with it. I feel like I’ve heard all these analogue acid house sounds before. I had this dream back then, like, we’re doing all this acid house now, what’s it gonna sound like in the year 2000? I thought by now we’d have some ultra-new, crazy sounds, not something that sounds like it’s 25 years old. I’m still waiting for us to get past that stage.  Sampling, early 90s style

Graham: I have conversations with younger people all the time about the culture of it all. It’s come back round so many times and I think it’ll keep coming back. There’s a certain quality of record that’s indestructible. If DJs are playing a mixture of old and new stuff, quality comes to the surface. Looking back to old Nu Groove records or Detroit techno stuff, it’s become classic. It has its own history now and it’s easy to dig back into that with the internet. So yeah, I approve of people studying the history of it and looking at the feel of those records, trying to find new ways of making emotional responses from computers. But it’s also a lot easier to make electronic music these days. It was a considerable investment in our day to start making that kind of music. It’s much more accessible now but the trick is to make your records stand out. Often it’s not about putting more things into the record but about particular feels and getting that sensibility to make a real standout record. It’s all down to feelings. I think it’s a really good move to look back towards what all the original records were about. It was all about atmosphere in clubs, it wasn’t about mixing one record into another. The novelty of that wore out in about ’91. Everything sounded really generic and the tempos were all the same. It just got really boring quite quickly. Gerald, after what you said on your blog recently we have to ask your thoughts on live dance music at the moment. Gerald: Yeah… I think, er… I think I’m still imagining that people are really dancing and they’re not off their heads. I’m really into the idea of people really listening to what’s going on and reacting to it, not just holding their hands up in the air when I hold my hands in the air. It’s almost like there’s a kind of pseudo… a false thing going on. People go out and seem to enjoy it but I find it really hard to pretend like that. When I’m playing live I’m really doing it. If I’m doing a tune and it’s not being appreciated I can change it round there on the spot. DJing’s a totally different game. It’s simpler but it’s still enjoyable, kind of like the difference between taking a photograph and painting a picture. I’m kind of getting to grips with the whole DJ vibe now.  BBC Manchester, 1988

Gerald: I’ll get it one day. Yeah, maybe if you keep plugging away and putting in the hours Gerald: Haha. Yeah… In terms of people who are doing something genuinely live with live dance music, what do you think of the current artists whose live shows are very much in the spirit of the old school all-hardware approach? You’re performing alongside Simian Mobile Disco on Saturday, for instance, and some of the younger guys like Karenn are very much in that same vein. Graham: I think it’s quite different in that it’s addressing dancefloor issues. With Rebuild we’re not particularly about making a record, if you know what I mean. When you see Simian Mobile Disco they’re playing their hits and there’ll be familiar music that you’ve heard DJs play. With Rebuild it’s kind of one step removed from that. Anything can happen. It’s almost like a return to an innocence. It’s a room full of people and you’ve got to make them do something. So, finally, are there any plans to record a Rebuild set and make it available to people? Graham: It’s not something we’ve discussed really. I think the minute you start thinking of it in those terms you start thinking about it differently. It’s not out of the question, but I think the throwaway nature of it’s kind of an important thing at the moment. It’s all by the skin of its teeth. Graham and Gerald perform Rebuild Live Acid Jam at Simian Mobile Disco and WANG presents Delicatessen, Fire, Vauxhall, London this Saturday (the 27th of October). Tickets are available from Fire. [Author: Greg Scarth. Photos courtesy of Graham Massey and Gerald Simpson] |

|