| Live And Direct | |

|

Electronic Issue 1 July 2012 Page ?? |

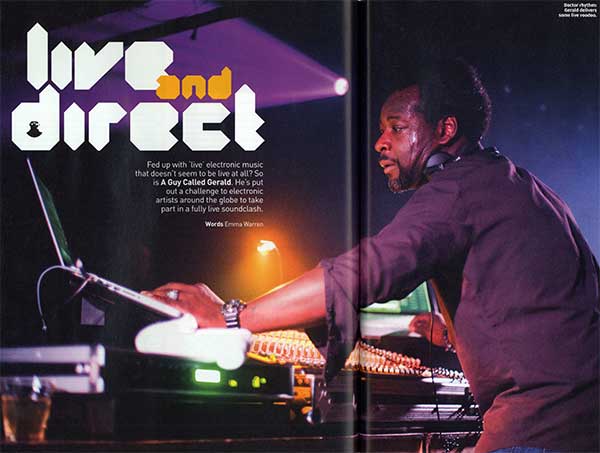

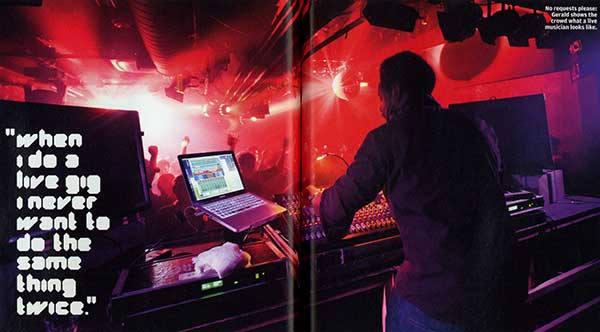

Fed up with live' electronic music that doesn't seem to be live at all? So is A Guy Called Gerald. He's put out a challenge to electronic artists around the globe to take part in a fully live soundclash.  A FEW WEEKS ago, A Guy Called Gerald was at a gig near his Berlin home. It was about the seventh time in a row he'd gone out to see a musician/producer/DJ throwing effects over one straight audio file and doing funny hand gestures. Gerald went home, got on his blog and issued a challenge. "I can't understand why I can't hear any decent live dance music," he typed. "I can't understand why there is so many people pretending they're making music... So this is an open call to all producers for a live soundclash. Bring whatever instrument, whatever genre, but most importantly bring the FUNK back to dance music. Let's wake dance music up." It's fair to say he hasn't been overwhelmed with responses, but typically of A Guy Called Gerald, he'd hit upon a truth: with a tiny handful of exceptions, electronic artists have been stuck in a bloke-behind-a-laptop rut for way too long. Gerald, on the other hand, has been playing his dark, funked-out, genre-busting rhythms genuinely live since 1988. Like a musical Rosetta Stone, he was right there at the first pulse of house music in the UK, making records that took the music into the charts (Voodoo Ray) and were accepted by his peers in Chicago and Detroit (Blow Your House Down). His 1995 Black Secret Technology album stands as one of the strongest electronic albums ever, and in tracks like 28 Gun Bad Boy (1991) and Boase Up (1992), he provided a vinyl-shaped bridge between hardcore and what would become jungle. Live music is just another arena where Gerald has earned his innovator stripes. "It's been how many years of this live thing?" he says over a glitchy Skype connection from his Berlin studio. "You put people in an easy space, they get tired or lazy and their skills drop off. I think that's what happened. You just have to stand there behind a computer. It's the equivalent of turning up at a club 25 years ago with a cassette and going through the motions with a graphic equaliser. I don't see the point." This suddenly takes me back to Manchester in the mid 1990s, when there was a rumour that a well-known but quite commercial house DJ had pressed his whole set onto two pre-mixed pieces of vinyl. We all thought this was hilarious. In Gerald's case, though, 'live' really does mean live. Usually, he goes out with two laptops, keyboards and an array of kit. At the moment, he's just about to embark on a set that takes him back to his original late-80s setup, using 808 drum machines, two SH-101 synths, a 303 bass synthesiser and "loads of analogue stuff". He says he's going to "jam live, everything from scratch, back to what I was doing in 1988", and it's telling that he's a bit gutted about this. "I kind of don't want to do it, but I want to show that something like this existed in real time, once upon a time," he shrugs. Futurists, you understand, don't like going backwards. Like he says: what's the point? We get talking about gigs he remembers and land back, memory-wise, at The Haçienda. It's the very end of the 80s and Gerald has got a three-foot table up on the stage. He's got synths and drum machines all along the trestle, from one end to the other, and he's skittering from end to end, staying in time with what's going on, checking out what's happening in the audience, feeling totally in the moment. "That's my ideal gig, really," he says. "It got to a stage by the mid 90s where people expected you to do a PA, not a live gig. They just wanted you to turn up with a DAT. I fell off from doing gigs at that point because I didn't want to pretend. I stopped doing live gigs and started DJing." I'm reminded of a story that John McCready, journalist and spin-doctor for Altern-8, told me once, about how his charges would send their mates to do their PAs. After all, who knew, or indeed cared, who was under the nuclear power station suits and face masks? And more to the point, who knew what Altern-8 actually looked like? Gerald's introduction to live electronic music came not from rave era PAs, but from the 1987 DJ International tour, which saw Frankie Knuckles, Marshall Jefferson, Fingers Inc and Adonis playing live at dates across the UK, including Manchester and Leeds. "They had drum machines, keyboards, singers... and it was live," he says. "There weren't so many people at the gig, but I remember seeing it and thinking it was totally fresh and really personal. They were playing the song I had on tape in my house, but they were playing it differently. That's one of the beautiful things about playing live. So that inspired me. When I do a live gig, I never want to do the same thing twice. There might be someone who's heard it before and they want to hear it in a different way." It goes without saying that electronic music has a brilliant, sometimes surreal roll call of performers, but there's a schism that appears at the end of the synth era and doesn't really repair 'til now. In the 705 and 8os, Roxy Music, The Human League and Japan took their analogue equipment and played on stage like stylish futuristic peacocks. Even Kraftwerk took the band template (people on stage, playing an instrument) as their starting point, although they transformed the space into a mechanistic, robotic factory floor. But when DJs took control, bands moved aside, for the most part, and performances became something that indie kids did. There are notable exceptions, although they make slightly odd bedfellows and I can't imagine a Venn diagram that includes these members: Aphex Twin, who DJed with sandpaper and performed with giant teddy bears on stage; Basement Jaxx, who amped up the visual impact by surrounding themselves with samba dancers and moved from behind the decks to play guitars; and Kieran Hebden, a higher level musician who made and performed two incredible improvisational albums with jazz drummer Steve Reid. If you didn't have a big budget or a lightshow like The Chemical Brothers, Leftfield or Underworld, acts defaulted to the unedifying sight of bloke, in T-shirt, behind a rack of kit. Or as Gerald puts it, a situation where you imagine Jimi Hendrix strumming away like he was in a country and western band just because that's what everyone else did. Gerald's earliest releases were recorded live. The way Voodoo Ray went down on tape was how he did it live in his attic in Moss Side. It was raw and instant. His determination to play live, even at hardcore raves, had an unexpected side effect. It provided a bridge into scenes as they was shifting, and in fact may well explain why he was able to make transitional music at some key points in UK music history. You couldn't play records from a just-emerging genre because those records didn't exist - but you could jam with the vibe, with a speeding-up tempo and a periscopic anticipation of what was around the corner, and boom, before you knew it, new tunes had been built. Perhaps, in the evolution of electronic music, live performance is our homo habilis - our missing link.  "That's a perfect gig," says Gerald. "Where you can get a response. That's the whole reason for lugging half a ton of gear around. Otherwise you might just as well put a CD on and have a drink and a cigarette in the corner." For Gerald, it also comes from wanting to dance. He started going to clubs as a 14-year-old, just so he could join in the moves, and he was heavily influenced by local dance crews Foot Patrol and Broken Glass. He studied contemporary dance at the Central Manchester Dance Centre and classical dance at the Royal Northern Ballet School. "I always wanted to dance and have something interesting to dance to. I wanted to feel that for other people too. If this loop's going on too long, I'm just going to switch off. It's going to be like Chinese water torture, it's going to make me numb. I want people to push things on. If you see people at the front, and their eyes look dead, you have to push them on." It's time for Gerald to switch off the connection and make his way to the airport. He's off to play the Mutek Festival in Montreal and time's looking a bit tight. We start wrapping up, talking about some of the new controllers that may revolutionise the practicalities of live performance, and about the collaborations he's got coming up with Diane Charlemagne (vocalist on Goldie's Inner City Life) and an Iranian drummer. Just before signing off, he describes his ideal live show, perhaps the kind of thing he imagined when he issued his soundclash challenge. He says there'd be a whole band up there on the stage, with everyone bringing their own sound. The artists would be comfortable with each other, jamming out, doing something that sounded like a mad techno track, then someone would switch it up and everyone else would follow. "Like those old movies with the jazzers," he says. "That's more than possible now." Check out A Guy Called Gerald's Blog at guycalledgerald.com [Author: Emma Warren] |

|