| A Guy Called Gerald | |

| DJHistory.com 16th March 2011 Link |

|

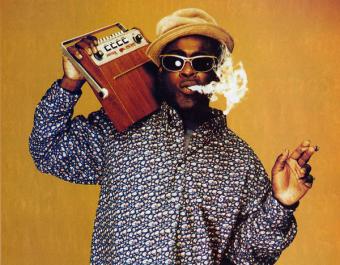

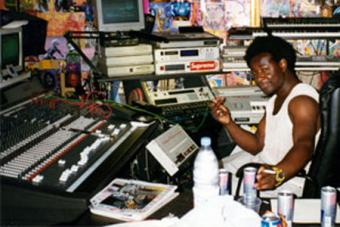

A Guy Called Gerald Gerald Simpson made one of the greatest dance music records of all time. Voodoo Ray defines an era and as A Guy Called Gerald, Simpson trod a path somewhere between down right dirty music whilst all the time pushing the boundaries of the technology at the time. DJhistory met the man to find out why he didn't get a penny for Voodoo Ray, how he had to do interviews from a pay phone and his eye opening introduction to the music business. All set against a backdrop of the Hacienda, Manchester's politics and ‘sort’ of borrowing library records What were the first records you heard that made you think “I want to do that”? I think it was the Arthur Baker remix of ‘Confusion', by New Order. He obviously put the 808 through separate channels and each instrument had a different effect. I somehow realised this and thought, “Wow, he’s doing that with sixteen tracks or something.” I instantly wanted a machine with multi-outs and to be able to go into a mixer and to record it down, treat each thing individually. Sounds like you were fiddling around before you DJed? Oh yeah. In my pre-teens I managed to acquire a load of car speakers and connected them together. One thing I remember was that the more speakers I connected together, the quieter it got, so I just tried different configurations until I got it to a way that I wanted. Then I got a bass off a friend and got an amplifier. I remember pulling an amp apart when I was really young and realising how it actually worked and I got a little reverb built into it. I then got hold of a really basic drum machine, where you had to make the spaces yourself and I rigged that up to play the bass, using the drums as an accompaniment to my playing. Which is what most of them were designed for originally. Yeah, they were all originally made for this vibe. I got hold of little Casio organs and I used to go to this shop called A1 Music in Manchester and they used to have a synth place downstairs where you could go and mess around with them. I’d spend all my Saturday in there messing around and kind of dreaming about owning one of these things and bringing it home. Were you spending spare cash on kit rather than records? I was into records but I didn’t have any cash at all basically. So everything was borrowed. I was collecting as many dance moves as I was equipment or records. I used to go to the library to find jazz records. I was totally into jazz funk in the early days. I would look on the back of a tune and Miles Davis records would have Chick Corea on the back and then I’d find Chick Corea and then I would see he was a part of Return To Forever, so I got this education. I wasn’t reading books; I was going for the vinyl. But I wasn’t old enough at the time to borrow the records from the library… You had to be eighteen didn’t you? Yeah so I used to sort of ‘borrow’ them. I remember when my sister turned eighteen, I tried to convince her to get records from the library for me but she knew I’d scratch them and she would have to pay for them. Anyway, in the end I managed to get a job carpet fitting, then I got a job in McDonalds and by then I was able to put money down on things like a drum machine. So you knew from a young age that you wanted to make a living out of it? Or was it just a burning desire to be creative? It sounds weird but I wasn’t actually thinking at all of making a living. It was purely a creative drive, purely because I’d hear something and I would have a burning desire to do something, not exactly the same but I’d be very easily inspired by certain things within music, especially if I heard something different. You were a regular at Legends weren’t you? Was that when you first started going out to clubs? Well, Legends yeah. But I started going to some youth clubs around Manchester where Hewan Clarke used to DJ. There was The British Legion and also this place in Brooks Bar, around Old Trafford called Saint Alfonsus and an old place called Dungeons. Hewan Clarke was a hero around Manchester. For sure but I didn’t really know the DJs in them days. The Jazz Defektors were big time for us and there were all these dance crews who we used to follow them around. I mean I knew of Hewan and Colin Curtis and all these guys and it was always a really big deal when they came into The Spin Inn, you’d see what they were buying and all that kind of thing. I got into a lot of tunes through Mike Shaft playing them on the radio and you’d dream of owning Japanese imports.  Sadao Watanabe? Yeah, all that kind of stuff. I’d go in there and flick through, and see the Japanese writing down the side, they were digitally mastered and you’d be like, “Woah!” I had friends who could afford those kinds of things and you’d go round and they’d do you tapes. I’d tape stuff off the radio. I’d try to do my own mix tapes actually from the radio because I had a double cassette player – that kind of helped with the music. I don’t know, it was really weird, it kept me busy but there was no conscious push, no master plan. After a while there was a plan to have a studio. One of the reasons was because I kind of got with this DJ crew after a while called the Scratch Beatmasters. This was around the time of Broken Glass wasn’t it? Yeah, we decided that we was going to go do challenges but I didn’t want to DJ as much, as back then it was cutting and scratching and I wanted to get more into having a studio. I remember one of them laughing at me, he was like, “I bet you can’t have a recording studio” and I was like, “I bet you I can”. From then I had a drive to record. I remember that was the conscious goal of having more equipment in the studio, or in the space in my mum’s attic. What was the first house record that you heard? The first track I heard, I don’t even know if I recognised it as a house track because everything was really mixed up. The first thing I can remember even before house would’ve been techno. ‘Clear’ by Cybotron was the first thing that I’d heard where my ears pricked up and I was like, “Wow”. It seemed more influenced by European electronic records than American ones? Yeah, it was clearly more orientated towards a European sound. I mean everything else I’d heard until then was more kind of rap orientated. And that was just totally ‘robot’. I was also listening to all sorts, Jean Michele Jarre and Vangelis, anything electronic really that I could get my hands on because that was what I was totally, totally into. And this blew me away and I was thinking of ways I could mix it whilst I was hearing it. Voodoo Ray wasn’t the first record you made, but was it the first house record. How did you end up making house records? Basically, I was making acid tracks for Piccadilly Radio. They used to have this demo show; I think it was on a Sunday with Stu Allen. He would do this thing where he’d play local demos and I was dying for people to hear my stuff. I used take it to Spin Inn on cassettes to let them hear it because they’d started selling acid house stuff as imports. By then I had this bass machine, a Roland 303. Actually first time I heard an acid track, I already had this bass machine and I heard something on the radio, I was like “Oh my god!” They were using the same bass machine that I had but were totally tweaking it out. Had you never heard that you could do that with the 303? Well I was going down the electro route with it. There were a lot of people in the electro world using 808s and SH101s and 303s. And so I kind of knew it from that world and it was used pretty straight. It was never ‘bent out’. So hearing it like that for the first time, I was just like, “Wow”. I could do that. So I sent in a lot of demos to Stu Allen and he started playing them on his show. This guy from Rham Records had heard the shows and basically through some friends, Chapter & The Verse, got in contact with me and said he’d like to release something. I had a load of demos and he gave us some studio time down at Moonraker Studios in Manchester. I had two days of recording so we recorded about five or six tracks and ‘Voodoo Ray’ was one of them, as well as ‘Blow Your House Down’ and ‘Rhapsody In Acid’. Four of the tracks ended up on an EP. Tell me about putting ‘Voodoo Ray’ together. Initially it was just a demo that I was making to play on Piccadilly. I’d already laid out the bassline and also the drumbeat and then I worked the 303 in later. At the same time I’d been doing this street soul type stuff with Nicola Collier who also did the vocal on ‘Voodoo Ray’. On the day, we got into the studio with two of the guys from Chapter, Aniff and Colin. They had this sampler in there – I’d seen an older version of it before but I’d never seen this new one. Anyway, I asked if I could put some of the stuff from my vinyl into the sampler and try it out. So I think first of all I put this thing from Negativland, I put some of their stuff into the sampler and other little bits and pieces and I kind of worked around that track, just messing around because it was the first time I’d used a sampler. I remember asking if it would be possible for Nicola to do some vocals over the top, so she sang all the way through, without sampling. Then I went back afterwards and said, “Can we spin the vocal into the sampler? And maybe just play the best part of the vocal into the track?” and so we spun one sequence of her vocals in and I remember putting the reverse thing on – I think I did that on everything actually because it was like the new tool. Meanwhile the vocal was playing and reversed and I was thinking, “Wow, shit! That sounds wild!” So we kept her vocals as it was, just raw – we didn’t take the best part, we just kept it. It was a good idea in the end, it was less mechanical, it kept this really weird flow. But the actual tone of her singing forward and backward at the same time created this weird, kind of hypnotic feeling. People were thinking it was some kind of Asian thing at first, because it was almost like some kind of mantra but it was just her singing backwards and forwards. I’d never worked with so many tracks – I’d been used to working with four tracks and bouncing them. Always bouncing things and losing quality. Actually, the studio used to be run by a famous comedian: Mike Harding! He’s a folk artist and comedian. He’s got a show on Radio 2 now! Has he? Yeah, it was Mike Harding’s studio and the guy who did the engineering was also the guy who looked after the studio. He was called Lee Monteverde and he was my first teacher in a proper studio. I was just like, “I want all the effects on!” So he showed me the ropes and basically left me there alone for maybe three or four hours. I didn’t know anything about counting bars or anything; I was just doing it on how it felt. There were some big monitors, Tannoys, at the back and we had some [Yamaha] NS10s at the front, I was just dying to just blast it through the big monitors but he kept on saying to keep it through the little ones and when you get a sound that you like, throw it through the big ones for a little while. He taught me this technique on how to keep it really clean but not make your ears tired. Be really frugal with the sound – you’re not having a party just yet basically. I think he was like sixteen or seventeen at the time and he was this mad Pet Shop Boys fan. He had to have everything clean. We had everything separated and all the snares and stuff were gated. There was stuff coming from the 808s and SH101s, some really noisy hums and he managed to clean it all up. I’d been into listening to all sorts of weird stuff, Jean Michel Jarre, Vangelis, Trevor Horn so that was in my head when I was making this track. Because I was used to working on cassette, my ears were trained to make it as clean and clear as possible and working with Lee made it even more crystal for me.  I’ve just been reading through lots of old copies of Soul Underground and there are loads of mentions by Jon Da Silva mentioning ‘Voodoo Ray’ well before it was released. What was the timeline? I recorded it in May ’88 and that whole time is all blurry for me because I moved from my mum’s house to a girlfriend’s in Oldham. She used to have a cellar and I managed to set up my equipment in there. Something happened and then she kicked me out and I ended up going to live with some other people and they couldn’t bear the noise so I ended up living in this squat in Hume. When you did ‘Voodoo Ray’ was that really inspired by trying to get on Stu Allen show more than getting it played at the Haç? It was a mixture. My main focus was the dancers. At the time there was this jazz fusion stuff but they’d kind of crossed over into dancing to acid house. Like the Foot Workers who were dancing in Sheffield? Yeah and there was this Manchester group called Foot Patrol and I had them in mind. It was like these really fast foot movements that I was into trying to make music for. When I first wrote the tune it was basically to be played on the radio. In them days time was totally different, I used to live, sleep and eat at the studio as well as going to clubs. I remember picturing the dancers but also picturing a big open space like the Haçienda. It was the first time I’d been in a space so big, I was used to smaller clubs with lower ceilings. When I was doing the drums in the studios and I could have just a reverb for the drum, so I'd be painting that reverb onto the bass drum and kind of imagining it on a PA at a big echo-y club. I think the Haçienda was what I had in mind at the time – and the dancers (it was the pre-E dancing by the way). I remember talking to Mike Pickering and he said to me that within six weeks of E arriving at the Hacienda, it had gone from being a black night to a white night? It totally changed, but for me it was always changing. I remember going there and seeing someone like Mantronix and there was a large percentage of black people there and seeing like The DJ International crew and that was a mixed crowd. I remember going down to that and being totally blown away because I knew all these tunes and got to see all these people. Your relationship with Rham sort of ended quite badly didn’t it? I mean, did they fuck you over or something? What had happened was that ‘Voodoo Ray’ was being distributed by a little company called Red Rhino that was going through the Cartel. The very first pressing, we did five hundred, it sold out straight away and they went straight to re-press. I don’t think they’d done that at Rham before. They were really excited and they were like, “Oh cool! We’re going to do the album next but we need to push this” and really pushing me to do more music. I was like “Cool! I don’t mind doing that, that’s what I want to do. I’ve got millions of tracks actually”. I was thinking, “I’m selling loads of them so there must be something coming back.” In them days my only goal was to have enough dosh to build a studio, especially after being in Moonraker I was like “Shit, if I could just do this non-stop, it would be great”. So I thought a bit of funding to do a new LP would be great. Around about this time, though, Red Rhino went bust so they lost all this dosh through there. But at the same time this guy [Rham owner] got a new car. But everything just seemed a bit dodgy. I ended up going to New York and working with this company, Warlock which was via Rham Records and by the time I’d come back everything had changed. Somewhere along the line, it charted and he got really excited and said that I should start seriously working on an album. At the same time I was living in this squat and I really needed some kind of financial assistance. I was going down to the local public phone to do interviews by now and I wanted to kind of step up a little bit. At least bus fare to the studio would’ve been cool in them days. I was doing this job at McDonalds and that kind of helped out a bit but then it got to so that I couldn’t work there any more but I was still not getting any money from them. So I thought the only way around this is to get some management. In the end I ended up finding some people down in London. So did you get any money for the sales of ‘Voodoo Ray’? No. I remember it got like this gold record or something? Yeah, it was the biggest independent selling record of the year. So I was just trying to find out if it would be possible to get one of these records. And I never got that. Obviously, I didn’t get anything! So you didn’t even get a gold record either? No, I didn’t. I didn’t get any of that stuff [Laughs]. In the end I kind of stepped back and was like, “Well, I’m changing. Why do I want this stuff? I’m kind of happy to just have enough to do what I want”. But still there were people ridiculing me saying, “Fuck, you should be loaded by now!” I was like, “OK, if you’re egging me on, I’ll try to get a bit of dosh out of it then”. So I kind of pursued it a little bit more then in the end I got a deal with Sony. How did you come to work with 808 State? Graham Massey was in a crew as well, wasn’t he? Well I started off with a crew of guys who used to come around to my house on Sunday and we used to jam out in my attic. We were called the Scratch Beatmasters. We also used to go down to Eastern Bloc, where we formed like the early version of 808 State. It was called The Hit Squad and it was a mixture of different crews. There was a crew of rappers from Altrincham, it was us the Scratch Beatmasters and then there was another body that we formed with me, Martin and Graham, which was called 808 State. Well, the Thermo Kings at first, then later called 808 State. We had a mixture of different ideas that we kind of pushed together, Graham had access to Spirit Studios so we used to go down and record stuff. At first it was breakbeat orientated because Martin was acting as ‘Creative Director’ in a way. I really wanted to stick with the electronic side of things but I was also used to breakbeats and stuff from the early hip hop days. A lot of the stuff by now – I can’t mention any names – had started to sound a bit cheesy for me. I wanted to keep it really underground, have a real heavy vibe to everything. But maybe it was a bit too dark for what they wanted. Well, he was obviously pushing towards chart stuff and I was totally not going for that at all. I mean I never really seen Foot Patrol or any of those guys dancing to chart music. They weren’t playing chart music at the Haçienda. I wasn’t inspired by that. But somehow I think that for one member of 808 State that was his end goal and I think he was a bit frustrated with me because I was totally going in the opposite direction to him all the time. But there was an element in what I was doing that he obviously thought there was a market for somewhere. I didn’t tell him about ‘Voodoo Ray’ at the time because I was scared that he’d try and take it over. So you were working on those two things simultaneously? Yeah, but I kept that separate. I think the first time he heard ‘Voodoo Ray’, he didn’t actually know it was me anyway [Laughs]. After a long battle – I was trying to get a bit of cash out of them for the Newbuild album after the Hit Squad thing that we did (which never really sold anything). I was naïve to what it was all about back then. I was like, “Well do you have anything that you could give me?” But he was just really adamant – that I’d have to wait, that these things take time. So I waited. I couldn’t even sign on for some reason. In the end I decided I wasn't going to work with him anymore, but somehow he kind of managed to wangle a Peel session, so I was like “Ok”. By then I think I’d done ‘Emotions Electric’ so I’d done a Peel session already (but I didn’t really tell them that). I was like “Cool, are we going to go down to London then?” and he was like “No, we’re doing it at Spirit because they want this vibe that we got”. So I went into the studio with them and we recorded maybe three or four tracks and I knew we only had a certain amount of time to do it so we recorded the tracks and I thought “At least I’ll get paid for this”. And I asked them a few times and got a bit frustrated and he got a bit frustrated with me asking so in the end I decided I wasn’t going to ask anymore. I forgot about asking until one day I turned on the Tony Wilson show The Other Side Of Midnight and saw them performing one of the tracks that was supposed to be for the Peel Session. So I was like “Ok….? So what’s this about?” Anyway, by then they’d obviously sorted out a deal so from then on we had this kind of battle. So are you sort of friendly with them now? Oh yeah, totally. We managed through my ex-management to work out a little deal. I just wanted the credit really. Them putting it out kind of made me feel like ‘Shit! I’m going to be another of them guys that just gets ripped off by the group. Fuck that, I want my name on it… you’re not just putting it out and saying ‘I did this’ so no way, I’m having my name on this”. So that was the main thing I was fighting for. In the end I got the credit and then with that I get royalties today. So that was my introduction into the music business [Laughs]. I remember you did the Ricky Rouge record, Strange Love and more house records. Why did you abandon it and start making drum and bass? Around about ’91, ’92, the house thing got really – I don’t know – just really silly. The acid thing just went out of control. You could picture I was really deeply into not just the acid side of it but the serious techno stuff and then before that I was into electro and electro funk and that. And it had gone from that to almost novelty records. They weren’t even using analogue machines anymore. I was a real purist and wanted it to be really ‘squelchy’ and deep. That disappeared and at the same time that it was disappearing I was hearing this new kind of stuff with breakbeats. At the time I was with Sony who wanted me to be doing this vocal stuff with big strings. They wanted another ‘Voodoo Ray’. At the time there was ‘Pump Up The Jam’ and some really commercial house stuff that was going on. I remember they tried all sorts, putting me with writing teams and stuff. Did you work with anyone that was well known in that period? Somehow, through some weird connections I ended up working with John Rocca. It was really cool because he actually really taught me a lot in the studio. He’s an amazing arranger and he taught me a lot of stuff about how pop music is made. But at the same time it was really frustrating for me because I just wanted to get down and jam and I wanted Sony to realise what I was about. I even went to the lengths of having my own imprint through Sony called Subscape. That’s what my music was coming out through; I didn’t want it as Sony or CBS. I want to show that there’s something that people are into… that there’s this really kind of dirty, hard sound and this is where I’m from and honestly people feel this when they’re in a club. But they couldn’t get it because it wasn’t showing the figures and that’s where they are: the numbers. By the end of the first album, I knew it was never going to work. There was no way I was going to be able to ‘mould myself’ into what they wanted, I couldn’t do it. I never grew up with pop music. I never entered a studio with pop music in mind. It was always to make dance music. Even today, I’ll scratch my head because ‘Voodoo Ray’ was never meant to be ‘pop’. It kind of came out that way in a strange way. It was popular but obviously not a ‘pop’ record, as such. It was never meant to be pop but it crossed over into that world and they got the wrong end of the stick. [Author: Bill Brewster] |

|