| DJ's Take Control | |

|

Flux Issue 54 May / June 2006 Page: 80 |

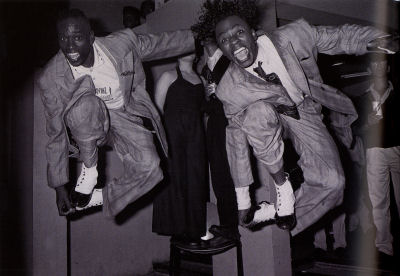

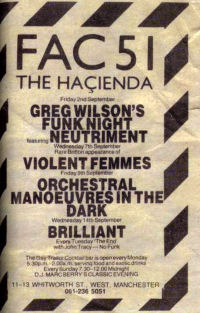

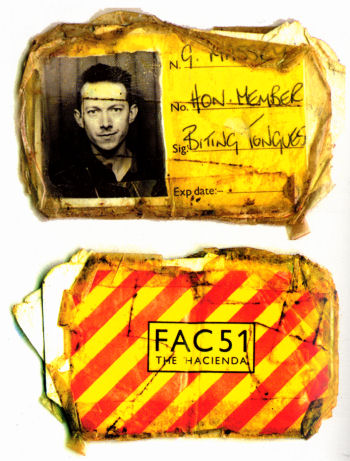

"You have to remember how grim Manchester was. It really was very dour. There was still a lot of that look that goes with The Smiths - people with big quiffs and checked shirts - and that was the girls!" 808 State's Graham Massey.  It has been argued countless times that the Hacienda was the birthplace of acid house during 1988's summer of love. But a new compilation of Hacienda classics tells the often overlooked story of what happened in the six years prior to the acid explosion. Having visited New York in the early '80s and experienced clubs like the Paradise Garage and Danceteria, Factory Records' management returned determined to recreate something similar in Manchester. As Ben Kelly's industrial designs were unveiled in 1982, it seemed that everything was in place to make this happen. However, musically there was a mountain to climb. Tunes like 'Don't Make Me Wait' by the Peech Boys and Cybotron's 'Clear', are now considered Hacienda classics, but back then were radical records. Not everyone in early '80s Manchester was geared up to welcome a new club with its eye on a brave new future.  "You have to remember how grim Manchester was," says 808 State's Graham Massey. "It really was very dour." The Hacienda was attracting new style magazines such as i-D and The Face, but as Massey says, "there was still a lot of that look that goes with The Smiths - people with big quiffs and checked shirts - and that was the girls!" Massey explains that before acid house, instead of breaking sweat on the dancefloor, punters would rather hang out in the bar, the club's restaurant or even - bizarrely - the hairdressers located in the basement. Contending with a huge, cavernous and often empty dancefloor became a huge problem for DJs. Converting a sceptical audience to dance music was to prove equally tricky. First in line was Hewan Clarke, an established name on the Manchester soul and funk scene. Next came Greg Wilson, a DJ who had built up a huge following in the north through his jazz funk nights at Wigan Pier and Manchester's Legend club.  "Mike Pickering and Rob Gretton were big fans of Legend," explains Wilson. "They saw it as the closest thing to the NewYork club vibe in Manchester." The Hacienda audience was very much the alternative, student type. To succeed in their quest to create a New York style club, the management needed the racial and cultural mix that Wilson attracted to Legend. As a result the DJ was approached to launch a new concept for the Hacienda - a specialist dance music night on a Friday. Initially the change in scene was extreme for Wilson. "Having become accustomed to working with a capacity crowd every Wednesday at Legend, The Hacienda seemed like a huge cold empty shell on the Friday," he explains. "There might have been a few hundred people in there, but they were easily lost in the vast space". Wilson's job was made more difficult by the club's awful acoustics and impractical DJ booth, located in an underground 'bunker' at the side of the stage. "You were actually looking through a slit at people's legs," he explains. "As a DJ you need contact with the audience. To get that I had to run up these stairs, stand on the stage and then run back downstairs again." This audience contact wasn't always encouraging either. "I remember being berated on a number of occasions for playing 'dance shit' and being asked when I was going to play some 'decent music'," says Wilson. "The indie crowd looked down on dance music at the time, viewing it as inferior to what they regarded as proper music - a band." While Wilson was trying to move the Hacienda floor, Morrissey was busy penning `How Soon is Now' with its refrain: "There's a club if you'd like to go/ You could meet somebody who really loves you/ So you go, and you stand on your own/ And you leave on your own/ And you go home, and you cry/ And you want to die". Not exactly the sort of mood Wilson was aiming for.  One key weapon that Wilson brought to the Hacienda was the Broken Glass breakdance crew. Club regulars quickly grew to love what the breakdancers were doing, making them more willing to be exposed to the music that Wilson had pioneered. Crucially the group also gave the club credibility for a black audience. Things gradually began to change. "The black crowd started coming, the indie crowd began to mellow. Bit by bit it was all conspiring towards the point some years later where it finally exploded." One of the kids to embrace the electro that Wilson was pushing was Gerald Simpson - later to become A Guy Called Gerald. In the early days Gerald viewed the Hacienda primarily as a live venue. "It wasn't until people like Greg Wilson and Hewan Clarke started to DJ at the Hacienda that I thought of it as somewhere you could go and dance," says Gerald. "Greg brought to the Hacienda the crowd that had been following him from club to club. Jazz fusion dance crews like the Jazz Defektors and others would go into the Hacienda and put on a crazy show and be even more amazing than whatever band that was playing. Most of the crowd had never seen this sort of dancing before or experienced the vibe." Gerald compares the energy that was created during some of these nights to the acid rush at its height. "It was great to dance at the Hacienda especially in the early days when there wasn't people just standing about waiting for something to happen or for their E to come on", he explains. Wilson remembers one magical night when London-based Newtrament played the Hacienda, bringing breakdancers with them. "They came with an attitude of `We're going to show you something'. What they didn't realise was that Broken Glass were at the front watching them." The gig ended up with a breakdancing battle. "I remember looking up and seeing Rob Gretton and all these guys hung over the balcony just absorbed and loving it. It was a real feeling of 'This is Manchester - we're in this together'".  But at this point these moments were fleeting. Graham Massey describes the schizophrenic nature of the club before the acid frenzy took over: "One of the first times I saw the Hacienda full was for an early Mantronix gig. That was the first time it had a really good atmosphere. Other nights you'd go there though, and it'd be really student orientated and all you'd get would be The Smiths and all that dreadful music by people like The Wedding Present." Still, these key moments did much to prepare the ground for what happened in that summer of 1988. As Mike Pickering took over Friday nights, Hacienda regulars grew to accept both electronic music and the concept of the DJ. In mid-1984 the DJ booth was moved to the balcony, symbolically and literally giving the DJ centre stage. What followed was one of the most important periods in the late 20th century cultural history of this country. But focusing solely on the acid house period would be telling only part of the story. "Too often people think of 1988 as dance music's year zero. However nothing happens by accident," says Greg Wilson. "Yes, the Hacienda became the right place at the right time, a phenomenal cathedral of dance - but it was a very long, hard journey." Discotheque Volume 1: The Hacienda, out on 22nd May, is the first in the Discotheque series of compilations from Gut-Active Records. [Author: Stuart Aitken] |

|

Hacienda classics Greg Wilson's Hacienda classics from 1983: Peech Boys - Don't Make Me Wait (1982, West End Records) Graham Massey's pre-acid Hacienda classics: George Clinton - Atomic Dog (1982, Capitol Records) A Guy Called Gerald's pre-acid Hacienda classics: Benny Golson - The New Killer Joe Rap (1977, CBS) Tony Wilson's pre-acid Hacienda classics: Lulu - Shout - "The New Year's Eve special". |

|