| SOUL SURVIVOR | |

|

URB Volume 10, Number 77 September 2000 Page: 100 |

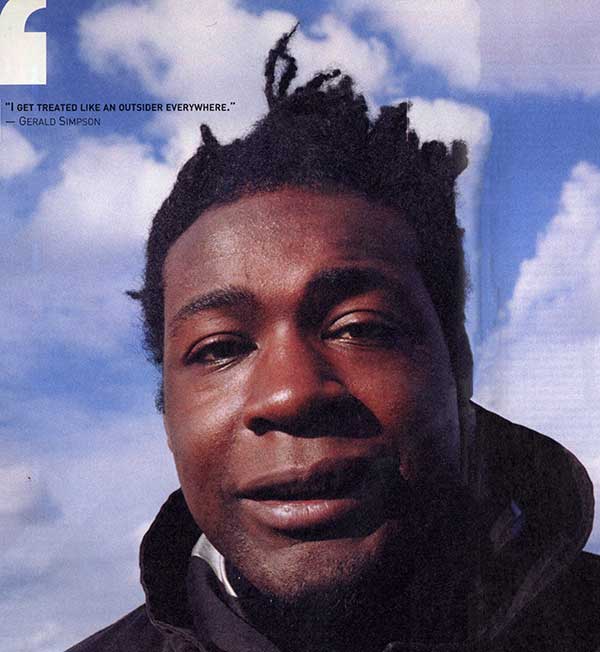

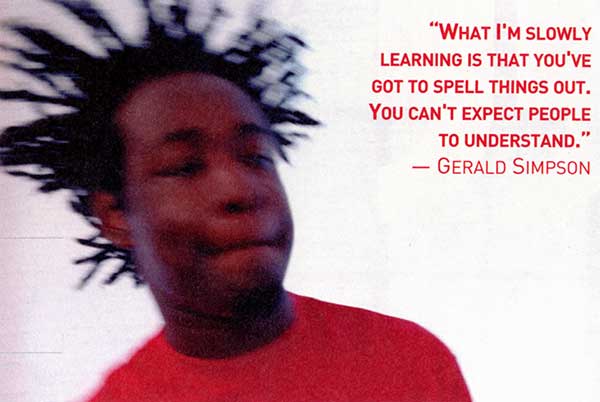

ACID HOUSE INNOVATOR A GUY CALLED GERALD HAS PUSHED SOUND IN VARIOUS FORMS OVER THE PAST DECADE, FROM BREAKBEAT TO JUNGLE TO ABSTRACT. AFTER YEARS OF STRUGGLE AND LABEL DEALS GONE BAD, GERALD SIMPSON SAYS ITS TIME TO HEAL. Two years ago, A Guy Called Gerald walked away from his London-based label Juicebox and into a new life. He took his studio and his music with him and relocated to New York. And now he's set to release Essence, his first set of new material since 1995's Black Secret Technology. As such, the album marks some-thing of a rebirth for an artist who has spent too long toiling in the shadows, but whose body of work acts as a series of beacons that reflect a marked progression within the culture. On Essence, the tribal polyrhythms that power his music have gone beyond the pumping blood-rush of the heartbeat. Now, as one new track, "The First Breath," indicates, his songs are actual living entities. Gerald Simpson furthers the Frankensteinian analogy of his technological creations by describing his tracks as "bodies." By this he means that the interplay between rhythm and melody, which in turn is built up from layer upon layer of textured sound, has enough complexity to trick the senses with the illusion that it possesses the "essence" of life. Its Simpson's belief in the infinite possibilities of cybernetic sound that fires his ire at the artifice of commercialism dressed up as creative progress that powers the British dance scene today, as it flips through genres like a colour chart made up of multiple shades of grey. "It's like they're spitting out clones," he says bluntly. "And that's easy to do if you've got a computer and a skeleton beat. You just fill the flesh of the melody around it. And then you can keep the same skeleton and put another thing around it and put that out. Because they're all the same tempo, it's cool for the DJ but not for some-one who wants a bit of variation. I'm not blaming any-one because it's part of the progression. It's part of what had to happen." But, as Simpson points out, this is the second time around for him. He helped innovate Britain's first chemically enhanced mutation of American dance music with acid house. The scene that developed around it was simply an unwanted distraction. "I was just like a head making music because I liked it," he says. "I didn't really think of competition. People thought I was freaky because I didn't cut plates for people." And the situation hasn't changed since he moved stateside. "I get treated like an outsider everywhere," he laughs. "I actually jumped off that whole house scene be-cause it got all samey," he continues. "When it started it was really stripped-down and anti-music. For me, it was something that was coming from Chicago and Detroit. It was really exciting and there was difference. If you listen to the stuff that was coming out of Detroit in '87/'88, you'd hear a compilation and it would have Juan on it, Kevin, Derrick, people like that, and all the tracks were different. If I hear a compilation now, it all sounds like the same artist. They've not got their own personality. That says to me that they're basically just plugging the machine in, turning it on and pressing record and leaving it at that. They're not putting any soul in it." Music is deeply personal to him. "There's certain things you can't explain in words but you can with music," he ventures. "I first tried to do that with 'I Won't Give In' and `Automanikk.' It was basically about all the shit that was going on then. I went over everyone's heads because it wasn't what people were into at the time anyway. But I went to Detroit recently and there were kids there who were into it and weren't even around when it first came out. What I'm slowly learning is that you've got to spell things out. You can't expect people to understand."  The music has been a constant release for life's pressure, pleasure and pain. A track like "Voodoo Ray," which receives rapturous welcomes on the dance floor to this day, communicates the overwhelming enthusiasm for Chicago and Detroit rhythms that first entranced Simpson when he heard them at the close of the '80s. And his long-unavailable 28 Gun Bad Boy album is like dance music's ‘There's a Riot Going On’. Bleak and claustrophobic, recorded at a low ebb, the rough-edged proto-jungle lashes out with primal power. But it wasn't until his next album, Black Secret Technology, that Simpson found a title for this force - "voodoo rage" - and contained it in a sustained assault on oppressive forces. By comparison, Essence is a retreat into an almost idyllic inner world - a virtual retreat from harsh realities and a safe haven from emotional battles where there are no winners, only losers. And despite the robust rhythms, there's a fragility and sensitivity to the music. But it's hard to get Simpson to talk specifics beyond the generalization of music and time periods, good and bad, that have dominated his life. Luckily, he has surrounded himself with vocal collaborators who know him well enough to speak for him, namely long-time friends Louise Rhodes (from Lamb) and Lady Miss Kier (who scats her way through the 'shroom-visioned' "Hurry to Go Easy"), and his brother David (who exhibits both rich soul vibrato and bad-boy ragga growl on "Could You Understand" and "I Make It"). Simpson also worked extensively with Wendy Page, a Welsh singer-songwriter better known as a composer of chart hits for girl-pop sensations Billie and Martine McClutcheon. Page's contributions are among some of the most direct statements on the record. Her voice curls in torrents of emotion on "Fever or a Flame," in which haunting memories bring the onset of a cold sweat. On "Multiplies," Page answers echoes of her former self and develops split personalities to escape a relationship that holds her in chains. Many of the songs on Essence seem to have a therapeutic quality to them. "I had to do this record," Simpson says, "because I was going off the deep end with the music I was doing before." At this point, he seems to be referring to the effects of the aforementioned label dispute, just one of a number of sour business situations that have stop-started Simpson's career since the early '90s. It seems that following the initial release of Black Secret Technology, Juicebox's general manager (who was also acting as Simpson's manager) loved high life and notoriety a little too much, and set about building a roster of artists the fledgling label could well afford. Deals were done for Simpson's music, but advances were spent instead on the label's upkeep. It got to the point, Simpson says, when the music stopped because equipment was broken and there were no funds to fix it. So he did the bravest thing imaginable and walked away from the label with nothing but his compositions and some cherished synths. Holed up in his new home in Brooklyn, Simpson was able to focus on fine-tuning Essence (which, before Goldie soiled all possible astrological connotations, was called Aquarius Rising). Despite having given away a label that had become synonymous with his output since the early '90s, Simpson seems to feel little bitterness. The suggestion that his music might become more aggressive to re-lease these kind of tensions appals him. Moving to New York has made Simpson acutely aware of how cycles of violence are perpetuated (and tacitly encouraged) on the street by market forces within American music. And he's horrified at the suggestion that his music would be used to express any negativity and continue the vicious cycle. "I've seen dead people lying in the streets in Brooklyn. They don't look very aggressive," he deadpans. "And there's 17-year-old kids who'll look right through you and kill for your shoes. They're going to grow up like that and miss out on so much because they've been pushed into that side of life." The only tracks that belie the languid feel-good factor of Essence (the upbeat, survivalist rhetoric and jar-ring afro-jazz of the David Simpson-voiced "I Make It" and the abrasive "Landed") are more exuberant and victorious than anything else. Furious drum patterns and snarling bass whip out an unchained melody on the latter, lashing against Page's distorted vocal. "Landed" is all about walking away unscathed from impending disaster (both mental and physical), and is a fitting close to the album. Simpson refers to it as a "healing" record. And as such it confirms that he's a fervent believer in music as an expression of a higher purpose, and a creator of sounds that reveal truths not only about ourselves but our place in the world. [Author: CHRIS CAMPION, Photos: BRIAN CARSON] GERALD WAS PHOTOGRAPHED AT HIS LOFT/STUDIO IN THE BEDFORD-STUYVESANT AREA OF BROOKLYN. |

|