| A Guy Called Gerald | |

|

URB Number 64 December 1998 / January 1999 Page: 48 |

|

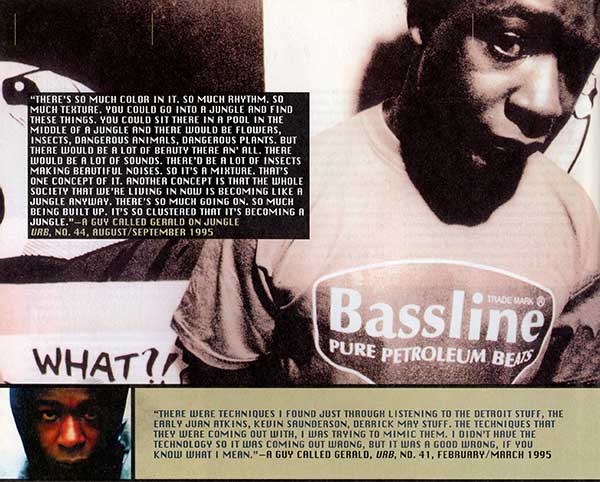

"There's so much colour in it. So much rhythm. So much texture. You could go into a jungle and find these things. You could sit there in a pool in the middle of a jungle and there would be flowers, insects, dangerous animals, dangerous plants. But there would be a lot of beauty there an' all. There would be a lot of sounds. There'd be a lot of insects making beautiful noises. So it's a mixture. That's one concept of it. Another concept is that the whole society that we're living in now is becoming like a jungle anyway. There's so much going on. So much being built up. It's so clustered that it's becoming a jungle." - A Guy Called Gerald on Jungle, Urb, No. 44, August/September 1995 "There were techniques I found just through listening to the Detroit stuff, the early Juan Atkins, Kevin Saunderson, Derrick May stuff. The techniques that they were coming out with, I was trying to mimic them. I didn't have the technology so it was coming out wrong, but it was a good wrong, if you know what I mean." - A Guy Called Gerald, Urb, No. 41, February/March 1995.  A Guy Called Gerald's everyman moniker belies the fact that in 10 years he has carved an idiosyncratic path through dance music. Amiable and relaxed, Gerald Simpson is chatting about sacred sound and metaphysics on a rooftop cafe overlooking a West London flea market. He's here for a few DJ gigs and to work on tracks for Finley Quaye's new album, but, for all intents and purposes, Gerald has moved stateside. He is currently based in Brooklyn, where he is setting up his studio. This new phase in his life coincides with the formation of a new label, Rotary Code. Early next year, he intends to initiate the label by releasing a three-CD box set titled Cryogenics, containing 10 years of archive recordings frozen in time. Simpson's relocation seems fitting, given that U.S. hip-hop and electro inspired his first home recordings with the Scratch Beat Masters, the hip-hop crew Simpson operated with MC Tunes. As DJ Screech, he handled production and scratch mixing for the duo's first single in 1986, "Back to Attack." By 1988, he had been turned on to the sound of Detroit's sleek futurism, the man-machine music made by the likes of Derrick May and Juan Atkins. Seeking to emulate them, he produced his own version and found fame with "Voodoo Ray," which remains the archetypal anthem of England's so-called Second Summer of Love. During a recent two-week stay in Detroit, Simpson re-acquainted himself with old friends. He collaborated on a track for Juan Atkins' forthcoming album and visited Mike Banks at his Underground Resistance headquarters, taking note of a new generation of kids who were transmuting their enthusiasm into music. "In the U.S., I don't think things move as fast musically," he comments, "but they give things a little bit more time and listen to the music. Whereas in England, people 'hear' music." Several times during the conversation, Simpson stresses the difference between the active and passive processes of "listening" and "hearing." He is more concerned with the latter and the intimate connection between the creator and his creation. "I've listened to stuff I've done in the past, and what I was feeling at the time connects with different notes and keys. The lower tones are grounded, the higher ones are things that you are unaware of." When Simpson starts breaking down the concept behind his new label, you know he's in deep. Rotary Code refers to the metaphysical connection between the mind, infinity and the circular patterns of nature. His research into these ideas boiled down to such supernatural subjects as out-of-body and near-death experiences. "It's meant to be like riding through the mind," says Simpson. "You see it as a movie but experience every emotion you've ever felt. And it's all in that much time," he says, snapping his fingers abruptly. The "mind-ride" could just as easily be a description of Simpson's history through music: snapshots that defy time propelled by the chronographic motion of constantly revolving beats. Living and working in Manchester up until the mid-'90s, Simpson was chained to a management company who held the purse strings on his Juicebox label and were content to milk his talent while paying him scant dues. He completed an album's worth of tracks released under the title 28 Gun Bad Boy, which provided a potent indication of the direction his music was moving in. Fuelled by the harsh reality he was living under in Manchester, the music was hard and dark with flashes of iridescent beauty. Tracks with titles like "Cops" and "Free Africa" were a torrent of musical fragments all screaming for attention - beats constantly cut across each other, dissonant electronic melodies rang like sirens offset by samples of sweet dub vocals. It was jungle in its raw form, acknowledging its debt to house, dub, electro and techno. The tracks that followed on Juicebox were titled to reflect Simpson's increasingly dark outlook; for example "Gloc" and "Dark As I Should Be," both of which resurfaced on 1995's Black Secret Technology under the more ambiguous "CyberJazz" and "Alita's Dream." By this time, he had extracted himself from under the thumb of his management company and moved to London, eventually setting himself up in a studio complex by the River Thames. Black Secret Technology, which was re-mastered and released in 1997, was another leap forward. A prodigious reader of all manner of arcane spiritual and scientific texts, Simpson's personal research had begun to slip into his music. "I was connecting things almost abstractly with the music," he says. Within Black Secret Technology's technically astounding cipher of beats and rhythms was a sonic thesis on lost arts, science and language set to the insistent pitter-patter of tribal drum patterns driven by a raw, percussive energy. "I think I've got a set way of working with the rhythm," says Simpson. "Usually I'll do the drums first and structure them in threes. If you're going to take it back to that tribal element, it'll be mommy drum, daddy drum and baby drum. It's all in that code." The feel he achieves is wholly organic, possibly due to the fact that Simpson still uses an old-fashioned sequencer rather than a computer running Cubase, a visual interface with sound. "I think a lot of producers work on the computer and lock the beat into time with the metronome, because they think if it's outside it won't be in sync. But the way that circular theory works, you can have a rhythm that drifts off slowly and comes back on. The track can stay in the same time, but the rhythm is moving out and in. If you get that, you've almost got like a rocking movement. You've got to be able to abuse the sequencer. Sequential timing isn't law." Although a critical success, Black Secret Technology never found the mass audience it deserved. This was because Juicebox just didn't have the resources to push the album in an industry now dominated by hoopla, and partially because Simpson's music has always been a few measured steps ahead of what is considered the Zeitgeist. Through '96 and '97, Juicebox focused on its roster of artists including Tamsin, Bushmaster and Sawtooth, while Simpson began work on his next album, Aquarius Rising - a starry precursor to the cosmic slop of Goldie's Saturnz Return. All the indications were that he was moving into song-based productions. Vocal contributions came from Lamb's Louise Rhodes, Wendy Page, Simpson's brother Custa and Lady Miss Kier, who became a close friend and confidante. It seemed that he was producing his most relaxed and accomplished work to date. The scatter-shot rhythms of old were calmed by a soothing wash of melody. The bass, which in earlier recordings sounded like the muffled sonic boom of multiple shotgun blasts, was a comforting cushion of subsonic frequencies. During the drum & bass gold rush of '97, Simpson signed to Island America, believing that the history and organization of the label would mean there would be a sympathetic ear. The last thing he wanted was to get caught up in a situation similar to the one he found himself when recording Automanikk, his debut album for Sony, who wanted to market him as a pop-dance sensation. But in an unfortunate case of bad timing, Simpson got dropped in a corporate reshuffle and spent the early part of this year trying to regain the rights to his as-yet-unreleased album. Following that debacle, he fell out with his former business partner, collected up all his music and walked away from Juicebox. "I've got a record box full of DATs, which I'm going through and burning down the best tracks onto CD," he says. A lot of the material covers his time in Manchester, ranging from early acid tracks through jungle/drum & bass to material he recorded for Aquarius Rising, some of which he is currently reworking for inclusion in the Cryogenics set. But does Simpson think his music has moved on from drum & bass? "I don't think I've moved on from there because I don't think I was ever there," he replies. "I'm definitely more into making songs now. I'm basically set on my own little path and always have been." It's all a long way down the road from the days when he was building sound systems in his mum's attic in Rusholme, Manchester, and constructing cut-and-paste hip-hop tracks with a basic studio setup in his bedroom. "I remember saying to one of the guys in Scratch Beat Masters, 'I'm going to have a studio one day.' He was like, 'Don't be stupid. You go to recording studios, you can't have one,"' Simpson laughs, knowing full well that technology has translated his dreams into reality. [Author: CHRIS CAMPION, Photos: EDDIE OTCHERE (MAIN) ! MATT FINKLESTEIN (INSET)] |

|