| Nubian Sound Systems | |

|

The Wire Issue 152 October 1996 Page: 26 |

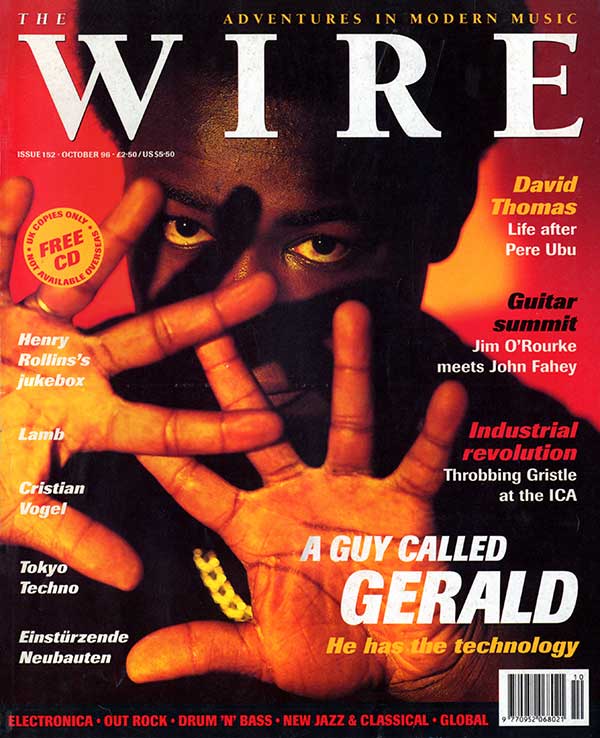

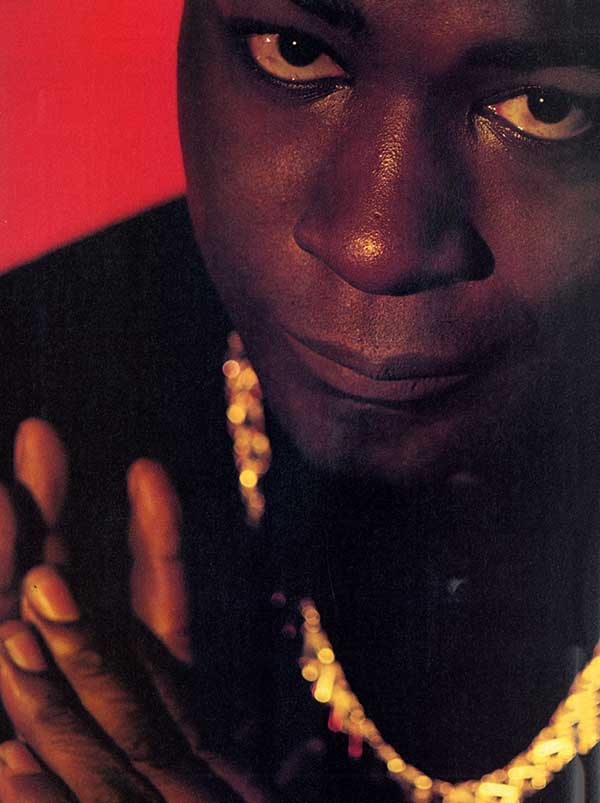

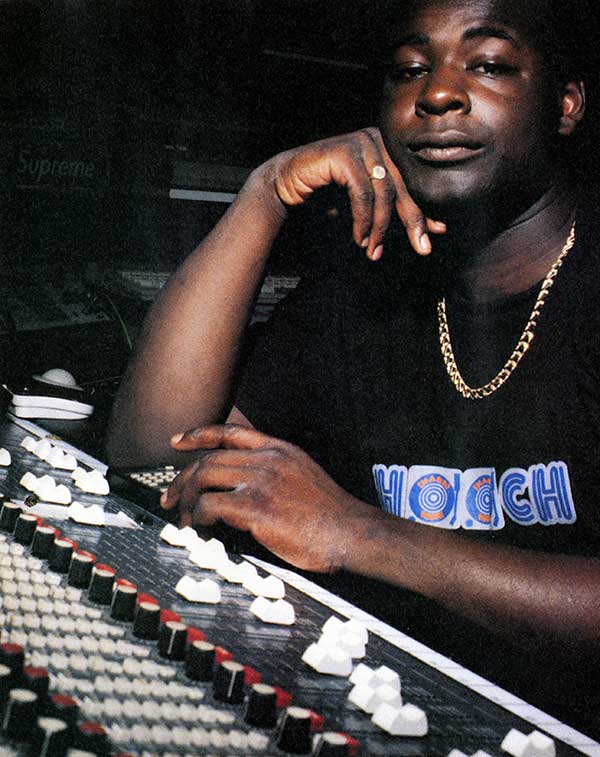

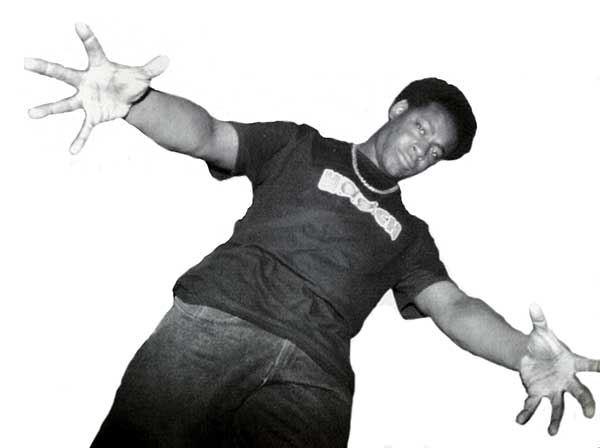

Ever since 'Voodoo Ray'' put a spell on the post-Acid House generation, A Guy Called Gerald has been exploring the world of black science fiction and technological overload from a studio filled with infernal sound machines. Guy Called Gerald's West London studio is a museum of the once cheap, poorly designed, make-a-quick-buck analogue Roland synths that African-American musicians re-configured into the instruments of the future, and of the neo-psychedelia of the 90s rave flyer that was born from this union of mass-production and street savvy. In its former life, Gerald Simpson's studio was where Dr Who was filmed. Indeed, with Gerald sporting a superfly afro, and the relics of dance music's past clashing with the futuristic musical output, Juice Box Studio has a certain Tardis-like quality. It's the perfect launching pad for Gerald's breakbeat alloys of his African ancestry and the metallic, space-is-the-place urges of the next century. In the liner notes to his 1995 album Black Secret Technology, Gerald wrote, "I believe that some of these trance-like rhythms reflect my frustration to know the truth about my ancestors who talked with drums." This idea that ghosts hover around the edges of drum 'n' bass seems to be prevalent at the moment. Omni Trio's Haunted Science album, Capone's unfathomably dark "Mysteries Of The Deep", the re-release of Origin Unknown's apocalyptic "Valley Of The Shadows", even the of dead and buried fusioneers such as The Yellowjackets by Goldie, Forces Of Nature and Aquasky. Just as the cut and splice architects of dub and HipHop gave new shapes to voices from the past, Junglists allow spectral apparitions to ride on top of today's breakneck rhythms through the technique of timestretch rig (changing a sample's duration without changing its pitch) and the sampler's ability to manipulate and shape-shift musical fragments. But for all of the mind-boggling technological sophistication involved, breakbeat science's fundamental goal is the reassertion of the two most basic musical properties rhythm and bass. "I was talking to an old drummer and he said that he was taught that the drum was the heart and the bass was the earth," says Gerald. "That's the foundation of nyabinghi drumming [the mystical percussion of Rastafarianism] .. Black Secret Technology was an exploration of that, I was using some African rhythms and at the time I was exploring the Nubians and reading about the Pyramids. I think that everything is coming around- I believe that the first civilisation will also be the last. I think that time is one big circle. Time is cyclical".  Perhaps with this in mind, Black Secret Technology is being re-released in a remastered version with extra tracks for those who missed the boat the first time around. "It fell through the cracks," says Gerald. "Nobody heard it I've boosted the bass for the dancefloor. The album is the Mothership and the singles are the landing crafts saying, 'Come with me. Listen to the album'" Also in the pipeline is a new album, due in the new year, which, on cursory listening to the raw tracks, sounds stunning Featuring live vocals (a first for Gerald) from Lamb's Louise Rhodes and, rather surprisingly, Lady Miss Kier from Deee-Lite in contemporary torch song mode, the album has a deeper, more detailed sound than its predecessor. "The new album is looking towards the new millennium," says Gerald rather coyly. "There's a track called "Aquarius Rising' which I did with Lady Miss Kier - she's really spiritual; if you want to know about the Pyramids, talk to her. I don't want to get all hippy and get my joss sticks out or anything, but it's looking towards the future and the new age... There's so much stuff that's being buried. Like the other day I saw that they found life on Mars and they were all blasé about it. It was like, 'Oh, by the way, they've found life on Mars'. I don't think that we're too far away from being visited by extra-terrestrials.' As Gerald hears it, these close encounters will be soundtracked by the unfettered immediacy of the breakbeat Where Black Secret Technology was largely a journey through melancholy dream states and a discovery of the textural possibilities of drum 'n' bass, new tracks like "Aquarius Rising" and `Mad Air' work because of the sheer exhilaration of their drum breaks. With its thrilling physicality, the break on 'Mad Air, in particular, stands out as it reconnects with the energy rush of classic breakbeats like "Amen", 'Apache', or "(Take Me Back To) Mardi Gras'. "I've been going back to some of the old breaks from my HipHop days," Gerald says about his new approach. "I've been running them backwards and putting all kinds of weird sounds on them, personalising them. . . When I was in New York there was this kid playing a rusty old kitchen sink and some pots and pans. I happened to have a DAT recorder with me, so I got some great breaks out of that." This return to the physical imperatives of velocity and boom while maintaining a commitment to explore the fringes of sound dovetails with Gerald's early musical development. As a young HipHop and Electro freak hooked on the chest-caving power of sound in the early 80s, Gerald would tinker with his primitive drum machines and vast array of customised speakers until he had enough oomph to rattle the foundations of his mother's flat in Manchester. "The first musical instrument I ever bought was a little Roland drum machine where you press for the bass and you tap on for a few steps," says Gerald. "I remember going down to a music shop and they had this new thing come in, Band In A Box. You had the drums and the bass, it was the Roland TR-606 and the 303 [the bassline machine responsible for the characteristic squelching sound of Acid House]. I had a little play around with it and I ended up buying it. I was just coming out of the Electro thing, there was still some Mantronix about, but there was a lot of Ice-T and stuff about and they were using the same thing, so I was trying to get the same kind of grooves going. Then I got more into the synthesis side of it and started tweaking the bass machine to get weird noises out of it. I heard the stuff coming out of Chicago using the same instruments and was like, 'Wow, so it's not against the law to do this type of thing.' I started to do what they were doing and got into that mode of the House groove." The result of this tinkering was the record that put British House music on the map, the eternal "Voodoo Ray". As is typical of the history of black music innovation, Gerald received next to nothing financially from the record's sales and now believes that the song is cursed. But while the title now seems prophetic of Gerald's belief that dark forces haunted its galvanising groove, it also suggests his preternatural mastery of mix-and-match studio experimentation. All of his early tracks were products of ludicrously cheap technology and an instinctive feel for its limitations and possibilities. "What I was thinking was that Roland had it together in terms of synching," says Gerald about his old devotion to the company that unintentionally kick-started Britain's dance music revolution. "There was no MIDI [Musical Instrument Digital Interface, which allows synths, sequencers, drum machines, etc to link up and work together] in those days, so I thought that if I had one instrument by them and wanted something else to work with it, then I've got to buy something else by them. "The Roland TR-808 is like a sequencer with its own built-in sounds," he continues. "The main feature of it, I think, is that it has a 16-step, automatically quantized pattern running through it. For a House tune, for that 4/4 beat, you'd put a bass drum on one, five, 13, 16, then hi-hats from one to 16, snare drums on one and 13 and that would be your basic House beat. From there, I'd build on that with cowbells, rimshots, toms; all the sounds in it are preset. You can tune them a little: you can turn the rimshot into a clavé, you can have the bass drum as one of those Miami booming basses [laughs] or have it really tight. In the early days, I'd hook up the SH-101 [an early Roland synthesizer] to one of the triggers on the 808 because the 101 has its own internal sequencer which can be triggered. I'd write a bass part into the 101's sequencer and I'd use a rimshot on the 808 to trigger the bass sound. Then I'd have a sequence already done in the 303 and I'd hook that up to the sync in-and-out on the back of the 808. All you'd have to do was press play on the 808, which was like the main brain of the system, it would trigger the SH-101 at the same time as the 303." This same spirit continues to influence Gerald's working process. As he says, "I have a lot of faith in serendipity. I'll use an idea as a base. Usually I'll put it all down on a Dictaphone and I'll use that to build on. There'll be a main theme to a track and then I'll build round that. I'll use a simple melody riff and lay that down and because I'm working on multi-track tape it's usually for about four or five minutes and it gives me time to think about what else to put down. It's mainly loops and I'll go back into the loops and re-edit them, take parts off the tape, put it back on a DAT, resample it and it all sort of builds... "I didn't get into sampling until "Voodoo Ray". I went into the studio with the track; it was still at a raw stage. I just kept the groove going for ages, and then got the vocalist in. I'd never used vocals before. I got her to do the vocals into the sampler. I was just totally machine, I didn't want any human element at all. I asked the engineer what I could do with her voice and he showed me how to reverse. I said, 'This is cool. What else can I do?' I got the rest of the samples and put them over the top." If Gerald's working strategies are symptomatic of a "throw things against the wall and see what sticks" approach, his musical influences are perhaps even more haphazard. After having his world turned upside down by Afrika Bambaataa's "Planet Rock", he naturally started getting interested in Kraftwerk ("I think I heard Afrika Bambaataa and Soulsonic Force first, so when I heard "Trans-Europe Express" I was like, 'They've ripped off Soulsonic Force."') and later Can, about whom Gerald says, "They were early drum 'n' bass I've remixed one of their tracks for Mute and when I was listening to them I was thinking, 'This is the 70s?"' But before his HipHop epiphany he began an unlikely association with David Bowie that continues today. Gerald remixing Bowie's "Ashes To Ashes" and his current single "Telling Lies", and the two are collaborating on a track for the Thin White Duke's next album. "There's some real weird stuff on "Ashes To Ashes"," Gerald claims. "There are these off-tones that work against what he's singing. This one frequency seems to come from these other unrelated frquencies. I think they call it heterodyning. I did something like that on "Voodoo Ray" without knowing it, where the bassline that sounds like a steel drum works against the main pulse of the track."  Are there any other rock skeletons in his closet? "Yeah, sure. I grew up in the early 80s so I was surrounded by it. I like that Peter Gabriel song, what is it? "Games Without Frontiers". Stuff like [Visage's] "Fade To Grey", I listened to all that until HipHop and Electro came along and blew me away." A more expected appreciation of American Swingbeat maestros Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis (the producers responsible for Janet Jackson's success) is a contributing factor to Gerald's finely detailed style. "I'd be doing a mix and I'd put one of their productions on and I'd be like, 'Wow, clarity'," says Gerald. "The quality that they were getting with the frequencies basically. The bass sounds were clear, the high end, everything was clarity. There were a lot of soul sound systems in Manchester playing that stuff and you could really hear it there. Before listening to their stuff, I was listening to dub and reggae and that is serious, just hardcore bass with a few highs and lows. But with them it was a lot of mids, a lot more graduation in the frequencies. I tuned into what they were doing and took it all on board." As with the majority of drum 'n' bass artists, though, Gerald's touchstone is the 70s heyday of jazz-fusion. But where nearly everyone else (with the rare exceptions of Photek, Roni Size and DJ Die) latches on to fusion's musicschool notion of 'quality' musicianship, Gerald aspires to the deconstruction/reconstruction of funk perpetrated by Miles Davis and Mwandishi-era Herbie Hancock. "I think that their grooves were a lot more advanced than what we're doing at the moment," he says. "I have this Herbie Hancock record with Chick Corea where they're doing live improvisations and every five or six seconds there's a different groove. We sort of work with one groove all the way through a track. Post-House, people are still locked into one groove for a tune. If you can get to that stage with many different grooves progressing through a track and still keep people interested, I think you can tell a lot more stories." The manic, cyclical, broken-glass breakbeat on "Mad Air" shows that Gerald is close to achieving his goal of creating polygroovalistic funk that plays with the sensation of hearing music move linearly through time and space. This quantum leap of musical possibility is no longer the result of an altered state of consciousness or a shift in the means of perception on the part of the listener, but a fundamental change in the nature of the musical document itself. Just as digital technology has shrunk the world to the size of a microchip, samplers, sequencers and digital editors have fundamentally altered the quality of sound itself and have literally turned the way music is processed and produced upside-down. Gerald's favourite piece of equipment is an Akai 5950 sampler. "I was just messing about with it and I remembered with "Voodoo Ray" that we reversed the loop," he says. "I had a look at what was going on there and found out that I could reverse things. Basically, I just started sampling things. There are two separate bands: one is the main band that goes forwards and then there's another that goes both forwards and backwards. So I started running some loops through that and it sounded really funky. I'd have something going forwards for a beat and then reversing for the other beat. You could create a sound that you couldn't quite recognise because it would be going backwards. I found that the sampler could be an art form on its own. As well as sequencing drums, you could actually take a break and totally delve into it, process some of the sounds, filter things out of it, reverse loops, have some loops going forwards, some going backwards, just getting more rhythmic. I got lost within it, you know what I mean? I'd save all that on DAT, then do a forward-reverse loop in the middle of that, put that down on DAT. Go back again, reverse loop it. I've got an old digital editor where I can take one of the reverse loops from the middle, put it at the start. Save that on DAT and reverse the whole thing. You come out with something [laughs] totally mental. Then I'll put that down on tape as a whole loop, say for four minutes, go back into the sampler and change the start point of the loop and then drop in over the main beat every now and again so you get stutters." Once again, Gerald's reliance on, and proficiency with, the sampler happened as a result of the circumstances in which he found himself. "Instead of using my Poland gear, I use Akai mostly now for sampling. That came about from playing live and synthesizers getting battered and damaged. My 808 was the heartbeat of my system and I didn't want to take it out on the road anymore. It's totally battered. I realised over time that the value of them was going up and people are really cherishing them. I bought mine for 1 150 or something like that. I could try to get another one, which is going to cost me a lot more, or I could try and sample the sounds from it. So I got myself an MPC-60 [an Akai sequencer] and sampled the sounds. They weren't as hard, but they worked live. Slowly, but surely, I got into using the sequencer and it became the heart of the system and I put the 808 into a cosy corner.' The new art of sampling allows for phenomenal levels of extraction, abstraction and magnification. As Gerald says, "Subtracting and processing, that's what it's all about." Coupled with the concomitant resurrection of the drone (see The Wire 151), Techno's new minimalism (listen to Andrew Weatherall's tight-fisted grooves) and the various permutations of dub, creative samplers like A Guy Called Gerald are indoctrinating a cult of infinitesimal musical detail. As this re-ordering of past music plays with memory and structure, drum 'n' bass has the potential to alter the experience of time in a manner more fundamental than simply speeding up breakbeats. "Say someone has created a drumbeat," explains Gerald. "They've done that in a space and time. If you take the end and put that at the start, or take what they've done in the middle, you're playing with time. With a sample, you've taken time. It still has the same energy, but you can reverse it or prolong it. You can get totally wrapped up in it. You feel like you have turned time around." The remastered version of Black Secret Technology with three new tracks, is out now on Juice Box (through SRD)  [Author: Peter Shapiro ] |

|