| A Guy For All Seasons | |

|

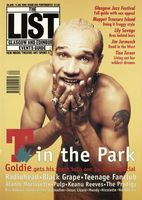

The List Issue 228 28 June 1996 - 11 July 1996 Page: 66 |

It's been a struggle, but A Guy Called Gerald is finally getting the recognition he deserves. He tells Rory Weller the details. If the mighty Sony Records hadn't pissed Gerald Simpson off quite so much, he would never have been in the happy position he's in now. After the phenomenal success of 'Voodoo Ray' in 1989, A Guy Called Gerald became one of the first dance acts to be signed to a major label. Happy to be in a position to make music free of financial pressures, he went along with the suits for a while and wrote from his heart, but pretty soon started to feel the strains of being just another product in a million-billion pound organisation. 'They put me in a backroom studio to make tracks, brought in a producer to learn what I was doing and then they'd push me out,' he explains. It just wasn't what he'd been used to. Through the 80s. Simpson had enjoyed a scattered creative process which was undeniably right for him. As well as making 'Voodoo Ray', he collaborated with MC Tunes, produced Detroit influenced techno and is now officially credited with writing 808 State's anthem 'Pacific State'. The way Sony made him work reminded him of his school-day piano lessons, when the teacher would whack the back of his hands if he played a wrong note: 'I found pain in structure. They [Sony] wanted a certain formula but didn't quite understand what dance music was all about. It's like trying to grow plastic trees - you've got to leave some things natural.' What he did manage to do at the time was complete the album High Life Low Profile, which contained direct messages to the company in the form of song titles, like the track 'Where do I Belong?'. Relations reached breaking point when Simpson went to the studio to put the finishing touches to the album, only to find the master tapes had been sent to Sony without his consent. His A&R man was hiding from him and his manager was convinced Simpson was headed to the company offices to beat people up so he could get the album tape back, which also contained a years work and material for another LP. 'There were a lot of people then with lives hanging on the line,' he says. 'They're lucky I'm an even tempered person 'cos, boy, I was ready to take out heads.' Curiously he soon found out he was no longer working for the company. Sony still had his tape though. For the next three years. Simpson camped in the studio working off his aggression. 'A lot of stuff I was doing then was "Grrrrrrr" — play it really loud and heavy, get the bass line to smash windows.' Free from the influence of drudge, he discovered a dance scene that was mutating and accelerating in a way he could grow with. Booked to play a live techno set at The Eclipse in Coventry, he had his set worked out until he heard the breakbeat DJs on before him. Instantly adaptable, he speeded up his BPM and played the bass line live. Taking this back to the studio later, he spun a break over it and emerged with the 28 Gun Bad Boy brutal drum 'n' bass album on his own new label Juice Box Records. That was 1993, and Gerald's dynamic creative force was visible once more. His continual variance would seem incompatible with the August re-release of 'Voodoo Ray', but it's because of the inexorable link between himself and the track that has called for the 'curse of "Voodoo Ray" ' to be revisited. His jungle remix is deep within the new world he has been inhabiting for the last four years. 'Drum 'n' bass will go at least half way through the next millennium,' he predicts. 'It is a summing up of everything in music as long as I've known it. It's the music that calmed the beast in me.' A Guy Called Gerald performs live as part of Strange Fruit at the McEwan Old Fruitmarket. Fri 28 June. [Author: Rory Weller] |

|