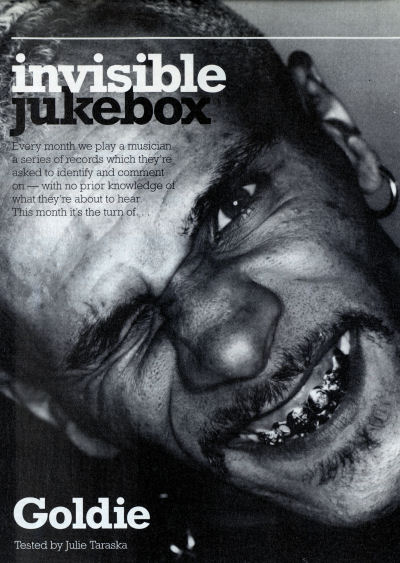

| Invisible Jukebox: Goldie | |

|

The Wire Issue 144 February 1996 Page: 40 |

No face is more identified with drum 'n' bass than the shining, snarling visage of Goldie. Born 30 years ago to a Scottish mother and Jamaican father, he spent his early years in Wolverhampton, being bounced in and out of care. His skills as a graffiti artist earned him a ticket to New York, where he starred alongside Afrika Bambaataa in Bombin', a Channel 4 documentary about urban street culture. After a stint in Miami, he returned to London in 1988. Disillusioned with UK HipHop, he jumped headlong into the rave scene, regularly attending Heaven's seminal Rage club and contributing artwork to the breakbeat label Reinforced. In 1992 he began producing his own tracks. A year later, under the pseudonym Metalheadz, he released "Terminator", a prototype of Jungle that introduced the technique of timestretching, stretching a vocal sample over different bpm ranges without distorting its pitch. In 1994 came "Timeless", a 21 minute single that fused dub, HipHop, jazz and Detroit Techno with processed breaks. His debut album of the same name was co-released by London/ffrr and his own Metalheadz label in September 1995.Since then Goldie has formed Razor's Edge, an imprint dedicated to 12" remixes of Metalheadz material; started a weekly drum 'n' bass club at London's Blue Note; and begun work on a script and soundtrack for a film based on Timeless. Goldie's jukebox took place in Providence, Rhode Island, the penultimate stop on his recent US tour with Björk. A GUY CALLED GERALD [After 30 seconds] This is fucking Gerald, isn't it? Yes, from 1990, when he was still making Detroit-styled Techno. People forget that rave was the bastard child of Detroit Techno. Detroit Techno was the fucking cutting edge. It was one of those genres of suppressed music that became a subculture. Detroit Techno has soul; soul that you can't get out of European Techno because it's four-to-the-floor. Detroit Techno even more so: it's the acceleration. I learned music backwards in that sense, where I had to learn what was Detroit Techno. I was given a manual, and then I had to read it And it was like when you read the first few pages, you don't understand it all, and you have to read more of the book to understand that page, that first chapter that's how I learned music. People like Mark and Dego and Gerald grew up within that music: people like me, I'm a prototype of the products, if you like, of all these people. Being a prototype, it's like being programmed to make music with no holds barred, with no history, just going, 'Right. This is the program. I know that program.' I'm trying to be like them, yet something happens where it turns into more than that. If the strength of me is based on all these people, then I become stronger. And then, whoever I hand it down to, becomes even fucking stronger. And who they hand it down to will be fucking all-powerful. That's why I am glad I was removed socially from the whole thing. Because I then had to go to America and miss out on a lot of things that were coming back on the rebound. I was in HipHop, New York, Miami - not in Detroit, not in Chicago - and a lot of these things were being created. Isn't that the same in any subculture? What happens is that you go back to go forward. You know what I mean? Why did you call Gerald up and tell him he had to come down to London? You're really informed, aren't you? I had a fucking burning need to, man. It was my job to do that. It was a mission. When I left the country, "Voodoo Ray" was massive. I didn't know who it was made by. Then I came back and people on the underground played me 28-Gun Badboy. I was like, `What the fuck is this?' There were a few Rebel MC things around, playing a spectrum of music: some Detroit Techno, Techno from Europe, the hybrid of rave and breakbeat, raw breakbeat. Before the word Jungle even came around, I remember a 10" on Kickin' Records; it was an eight-track recording, and it went Jungle, jungle duh duh duh duh". It was a tribal thing then. It was about urban jungle. It had fuck all to do with race. It had elements of that, because our families - well, my Dad's Jamaican, come in the back door of the UK, it's part of our culture, you know. But as far as that's concerned, when it comes to Jungle, I can take you back to 10"s, a 10" that Grooverider did - it went "Grooverider, groove groove rider doo doo dood000doodo" It was crusty as fuck: it was being played among high production European stuff, and it had an appeal because it was trash, it was street. But I'm getting off the point The reason I called Gerald was that Fabio was playing this stuff and Groove was playing this stuff, and I said, 'Who is this Guy Called Gerald?' And because Fabio and Groove had such a history in Gerald, I was like, 'Have you met Gerald?' I made all these connections that I had to make, but this one connection was outstanding. Where's this Guy Called Gerald? Well, he's a Northerner, so I'm a Northerner. It was a lot to do with that as well. I found a number and tracked him down, phoned him up, said, 'I don't think you know what you're doing. I don't think you know what your music's doing. Regardless of how overground things have become, people on the underground have a lot of respect for you, and you're doing a lot for me with the tunes you are doing right now.' Because I know what it's like to be in a bubble in the middle of nowhere, doing that kind of stuff. I didn't think he knew the impact So I said, 'You've just got to come down...' [It's] really important to make these connections. The technology became timeless. We used to look at things like this, and we'd see the spectrum. We could see things in perspective, and t was possible to make those connections. And if you made those connections, it squashes history. It makes people realize that you can reach your peers within a certain time. Think about screaming Beatles fans. We are products of our environments. We are disposable heroes, in that sense. And that was really important for me to make that connection with Gerald. I knew that the energy he had was no different than the energy that I had for the music. We all listened to Gerald. We are all windows and mirrors, we reflect around each other: all catch the light at the right angle; keep spinning around. No one person can say they started Jungle, but everyone can say they contributed to it. [Author: Julie Taraska] |

|