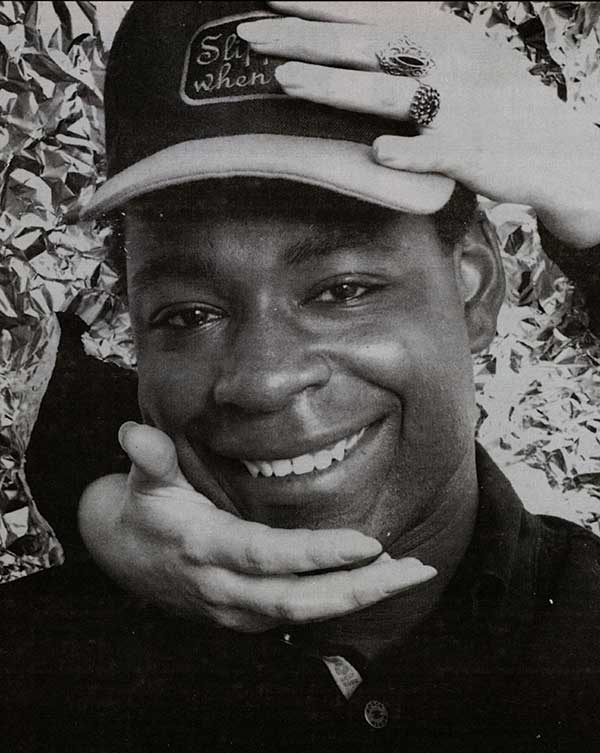

| Wicked, Guy! | |

|

Melody Maker 25 March 1995 Page: 27 |

A GUY CALLED GERALD is at the forefront of junglist innovation and future-shock technological experimentation. A guy called SIMON REYNOLDS joins him in virtual space. A guy called PIERS ALLARDYCE traps him with a photo beam. IN MANY WAYS, GERALD Simpson has the absolutely stereotypical profile of your average artcore junglist. Steeped in early Seventies jazz rock (Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, etc), Gerald flipped for electro (Africa Bambaata, Mantronix), then tripped out to acid house and Detroit techno. His first creative efforts were in The Hit Squad, a Manchester hip hop collective from whose cadres 808 State coalesced. Gerald was briefly a member of 808 (who, non-coincidentally, were also fusion freaks), and actually co-wrote their biggest hit "Pacific State". By then, Gerald had his own thing going, having scored a Top 20 smash with "Voodoo Ray". This slinky aciiied-samba reappears in drastically remodelled form as "Voodoo Rage", on Gerald's brand new, unspeakably brilliant album, "Black Secret Technology". It turns out that the song was a' ways meant to be called "Voodoo Rage", but didn't have enough memory in his sampler and had to chop the "g" off.. After "Voodoo", the logical thing for Gerald would have been to follow all the other Detroit buffs up the funkless cul de sac of "electronic listening music". Instead, after a frustrating period signed to major label Sony, Gerald discovered the glory of breakbeat. Originated by James Brown and the Meters, sampled by hip hop producers, breakbeats are what enabled a generation of post-rave producers to move beyond the 4/4 monotony of house, into the multi-tiered, hyper-syncopated rhythmic psychedelia of drum'n'bass. "Originally, I was into drum machines, I used to hate breaks. But then I discovered that with a sampler you don't just have to take a break and loop it, you can chop it up into segments, recombine it, enhance and stretch the sounds. Basically, you can turn a couple of hits into a whole drum solo." Metalheads' Goldie had contacted Gerald, dragged him down from Manchester to Rage, London's legendary 1991/92'ardkore club. Gerald realised that hardcore was an emergent subculture that was totally British, and he wanted in. "The whole vibe was totally different to what was going on in Chicago. I realised there was no point in me trying to sound like American house. Jungle was also like touching ground with my own personal roots, cos my parents are from the West Indies. For me it was like, 'I'm still a real person, I've not been castrated by Sony'. Cos they'd wanted me to make Hi-NRG style music." GERALD's first efforts were ragga-influenced tracks like "28 Gun Bad Boy", but gradually he evolved towards the artcore end of things. In early 1995, the term "jungle" has already been outmoded by the music's onward and outward diffusion. That familiar matrix of influences, fusion/electro/Detroit, is pushing ",jungle" in all manner of astonishing directions-the cyber jazz strangeness of Photek and Alex Reese, the hyper-soul "hardstep" of Hidden Agenda, the lambent aqua-funk serenity of LTJ Bukem and his cronies. On "Black Street Technology", Gerald dabbles and daubs in all these different shades of the state-of-artcore spectrum. But his stuff is still too weird to get played at Speed, Bukem's Thursday night salon for the drum'n'bass scene's inner circle of cognoscenti. From Tricky to Goldie, from Earthling to Droppin' Science, Britain's first generation of B-boys have come of age. And the striking difference about trip hop and artcore jungle vis-a-vis US rap, is that race is not the crucial determinant of belonging. Instead, what unites da massive is a shared attitude towards technology, an impatience to reach the future (hence Omni Trio's "Living For The Future", Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse's "We Are The Future", Red One's "The Futurism", ad infinitum). From the orgasmatronic rapture of "Energy' to the cyborg paranoia of "Gloktrak", Gerald's new LP is virtually an essay (non-verbal, bar the odd sample) about the bliss and the danger of techno-fetishism. The title, "Black Secret Technology", expresses this ambivalence perfectly. Gerald heard the phrase on a TV talk show about government mind control via the media, where some kind of witch woman used the word "black" to denote malign sorcery. But Gerald detoured the word to evoke the science fiction fantasies of black pop's maverick tradition - Sun Ra as Saturn-born ambassador of the Omniverse, Hendrix landing his kinky machine, George Clinton's Mothership taking the Afronauts to a lost homeland on the other side of the galaxy, Afrika Bambaata's fetish for Kraftwerk and Nubian science, Juan Atkins and Derrick May's cybertronic mindscapes. At this fraught fin de millennium moment, technology appears both as instrument of domination and of resistance - machines can both castrate and superhumanise you. Gerald belongs to a subculture based around abusing technology (jungle's all about doing things with machines unintended by the manufacturer) rather than being abused by it. And it all goes back to his childhood. "I got a tank for Christmas and it played a tune, and I just had to know how it worked. I took a knife but I couldn't get these mad screws to open. So I heated the knife in the oven and sliced through the plastic, and ripped the tape recorder out. I just had to know." Gerald still has that small boy's confidence about technology. As with a lot of post-rave producers, there's something vaguely autoerotic, verging on autistic, to his techno fetishism. When I ask him if he ever feels like a cyborg, in so far as his machines are extensions of his body that give him superhuman powers, he frankly admits that working in the studio, "its like your own world, and you become the god". LIKE a lot of artcore producers, Gerald's eager to extend his dominion from the aural to the visual; he's hungry for the new frontier of virtual reality. He dreams of a machine that could convert sound into visuals. You'd feed a sound in and the computer would turn it into an image on a screen. Then you'd manipulate that vision and turn it back into sound. There's still scope for new things using sound. But hooking into the visual would make it even more interesting. Especially for kids nowadays, who're into computer games." On the album, "Cybergen" is all about an imaginary drug that's basically virtual reality. Says Gerald: "The vocal goes, 'It takes you up, down, anywhere you want to go'. It's a drug where you're in total control of the experienceif you wanted a steel globe floating about, then going purple, you'd have it. Then the vocal says, 'It's too late to turn back now', and that's making the point that it's no use saying we can't cope with this technology, that it's going to ruin society. Cos the technology's already here. You either cope with it or you're lost. Kids today are already totally hooked into it. Kids today are frightening. I grew up with records, and now I know how to manipulate records. When today's kids grow up, they'll now how to manipulate the visual side of it." So do you think people will lose interest in music? "Yeah, sound will just become a small part of it. I can't imagine a kid today just sitting down listening to an album. It's progressions, innit?" Feeling like a fogey, I quibble: isn't part of music's magic the way it makes you come up with your own mind's eye imagery? Gerald's chirpy response is that with CD-ROM, you'll soon have the power to create your own graphics. But I counter feebly, who actually has the energy for all this interactive self-expression? "Not people who grew up in our era. But kids today, given 10 years, they'll be on it." PEOPLE from "our era", even those who are getting on-line, feel a deep anxiety about the digital revolution. The sense of being outstripped by technology's exponential development has even penetrated the subconscious: once, schizophrenics imagined loss of control in terms of demons and incubi, now they rant about microchips implanted behind their eyes or satellites irradiating them with a brainwashing beam. But Gerald is gung-ho about technology's empowering potential. He takes a boyish delight in the sheer "deviousness" of the ever escalating, technomediated struggle between Control and Anarchy. "There always ways around it. Say if someone was scanning into this room with a directional microphone and listening to us, we could scan them back and find out their exact location. Your phone can be bugged, but you can get devices that scramble the signal. When we were at school, we used to fiddle fruit machines. They always came back with some new trick to stop us, but we always got round it. We'd find ways to get credits on space invaders machines. It was like ghetto technology." 'Black Secret Technology' is out now on Juicebox [Author: SIMON REYNOLDS, Photo: PIERS ALLARDYCE] |

|