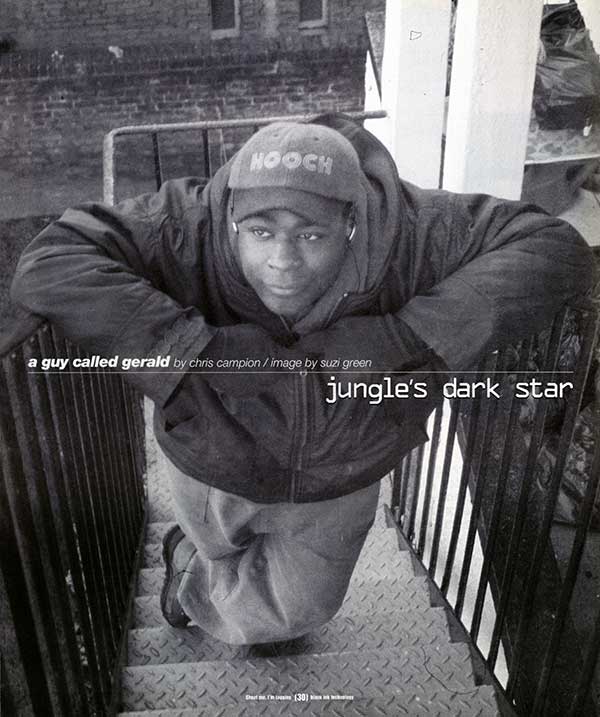

| Jungle's Dark Star | |

|

URB Number 41 February / March 1995 Page: 30 |

BLACK SECRET TECHNOLOGY: It sounds like a top secret and very sinister military project. It probably was until Gerald Simpson, aka A Guy Called Gerald, intercepted it from some stray transmissions. It's the name of his new album. "I was watching this show, a late night TV chat show," Gerald explains, "and there was this totally mad woman on it and she was going on about the government using Black Secret Technology to brainwash people." He chuckles at the thought of it but then assumes a serious tone. "I thought it had a nice ring to it. I thought that kind of angle, technologically, is where the old media system is coming from. Everything that is out there commercially has some kind of brainwashing technique or something within it. So [the album is] basically a form of expression to say, 'Yeah, look we know where you're coming from and we're not gonna be derailed from our missions."' Gerald is utterly defiant when he says this. Many independent artists probably have stories of being exploited by businessmen, most never get told. It's almost as if there's another secret history of the music industry. Nearly all of the pioneers of the music we cherish today never received the money they've earned. Even so they remained dedicated to their art whatever the circumstances. In 1988, the so-called second Summer of Love, Gerald was one of a select few artists who gained worldwide recognition through the media focus on the music coming out of Manchester. It was and still is for "Voodoo Ray" that he is best remembered. Gerald had got hold of some basic equipment and after playing around with this setup to record some hip-hop he got turned onto early acid sounds that he heard on Piccadilly Radio. "Then I got bored with the acid sound and turned on by the more sophisticated sound that was coming out of Detroit," Gerald recalls, "I'd got hold of a little SH101 keyboard and was trying to do what they were doing with D50's with just this little keyboard, a drum machine and this acid machine. That's what 'Voodoo Ray' came from. It was basically just trying to do what they were doing in Detroit. There were techniques I found just through listening to the Detroit stuff, the early Juan Atkins, Kevin Saunderson, Derrick May stuff. The techniques that they were coming out with, I was trying to mimic them. I didn't have the technology so it was coming out wrong, but it was a good wrong, if you know what I mean." The attention garnered from those initial releases eventually led to a deal with Sony Records. There Gerald found his creative flow stilted as he was forced to work with in-house producers and engineers. "Basically they wanted to channel any kind of emotion and experiences that I picked up through traveling, any kind of expression they wanted to channel into a little pigeonhole so they could market it in a certain way. Which I thought would be the other way 'round. That I would actually create something and they would have the master plan, the brain, to actually sell it to people in a certain way. I found the only way that I could do it was myself, to actually create my own label, get people really into listening to music to listen to it and take it from there." So Juice Box was formed, some three years ago. With his share of the money from the Sony deals Gerald also built Machine Room Studios. His management team set up a distribution company for Juice Box recordings, and in the process started to become overzealous in their treatment of Gerald. "Basically I was living with them from day to day. The first Juice Box singles were there to finance me living and eating. I'd give it to them and they'd give me five hundred quid to live on. That would have to pay everything. It was a nightmare. It was like, 'Oh no, I've got to get four tracks done.' It must have worked out that I was doing one track a week. So four tracks added up to a month an' that's the way I seen it. I thought, at least at the end of the month I can eat because I'm gonna get paid. It was basically take as much as you can get without me actually dying of malnutrition. It was really evil. When I actually sat down to work it out it was like, shit, slave labor! I was living in a house with no heating, it was freezing. I'd go into the studio and have to turn everything on and work to keep warm. Which was cool 'cause it paid the rent at the end of the day. It was a really weird situation where I couldn't really see a way out of it. At the time it was like, shit, am I gonna have to keep on doing this. How far can I shrink? If they started to say these things ain't selling, where do I go from there? If I couldn't keep putting these things out and getting my money for 'em, where do I go from there? Do I sell my equipment and get a job in McDonalds? There were loads of things going on in my head. I had to break free of them." At the time he wasn't even allowed to speak his mind in interviews, which were doctored. Gerald saw his chance to explain his situation when a journalist from Germany called him up to do an interview, wondering what Gerald had been up to in the intervening years since "Voodoo Ray." "Somehow he got through the vetting and got in contact with me direct. So basically I just told him how it was, thinking it would get back to me first. But he sent the finished interview to them. They were like, 'Oh shit, we've been exposed.' They were down the phone to me saying, 'Well, you can fuck off!' I've got it on tape, 'cause I used to tape all my phone calls. It was like, 'Look because of this interview we're not gonna' pay your mortgage anymore so you can sit there and fuckin' starve to death.' l was like, 'Well, shit, see ya. I don't want anything to do with ya anymore if that's the way you think."' Gerald was left battle-scarred but still fighting with his record label intact and a body of material that speaks for itself. There have been twenty-four releases on Juice Box to date since and looking back it is clear that left to his own devices, holed up in his studio with only the will to make music and survive. Gerald was creating a whole new language. The legacy of the first three years of material from Juice Box is overwhelmingly stark and dark but still undeniably beautiful. From the early tracks collected on the 28 Gun Bad Boy CD which fused hyped breakbeats with Gerald's soul-inflected Detroit influences, to later tracks like "Gloktrak" which feel so overpopulated with overlaying textures they are in danger of exploding-they sound like the threat of terrific violence. This month, Gerald will release his Black Secret Technology on Juice Box. An album that is a powerful and mysterious voyage through Gerald's last 4 years. Gerald used his past as a reference of house and acid inspired roots to find the gorgeous chaos and fluidity amongst the broken melodies and hardcore beats of jungle. While some may use the term "ambient jungle," for its slow ethereal qualities, the album's brush of rebel rhythms and stirring synths are still powerful enough to evoke a traditional boxing ring soundclash. Gerald is set to revolutionize the idea of jungle. In the midst of talk about a jungle revival, he's already set the genre on its ear with raw forlorn emotion behind the cascading pattern of beats. His futuristic rhythms rip into the speaker cabinets -on their own, solid and totalitarian - which immediately turn to liquid, flowing and soulful. Tracks like "Finley's Rainbow" or the careening exploration, "Survival," signal a new generation for the junglist - mixed with the roughened beats is easing flutes and string sections with angelic voice loops, almost suggestive of his earlier self. Propelled through his subtle Chicago and Detroit influences is a reminder of where A Guy Called Gerald started. It seems to speak volumes that the track that started it all for Gerald, "Voodoo Ray" has been dusted off and reworked (using Black Secret Technology) as "Voodoo Rage," and the story behind how it made the transformation is spooky to say the least. "I got all the old samples out and started working on it. I got to the Voodoo Ray sample, and I forgot all about this but at the time when I put it into the sampler it was Voodoo Rage but because the sampler that I was using in those days didn't have much memory it ended up as Voodoo Ray. So it chopped the G off, totally, just chopped it off. And I just forgot all about it. So when it came back to doing Voodoo Ray I put all the samples in. Pressed on that sample and it said 'Voodoo Rage', and it all came back to me. So I thought, well, yeah it's gonna be 'Voodoo Rage' now, forget about Voodoo Ray. In a way personally, for myself, it was saying I've progressed. I've got the sample now. I've got the technology." [Author: Chris Campion, Photo: Suzi Green] |

|