| Return Of The Gerald | |

|

Mixmag Volume 2, Issue 45 February 1995 Page: 54 |

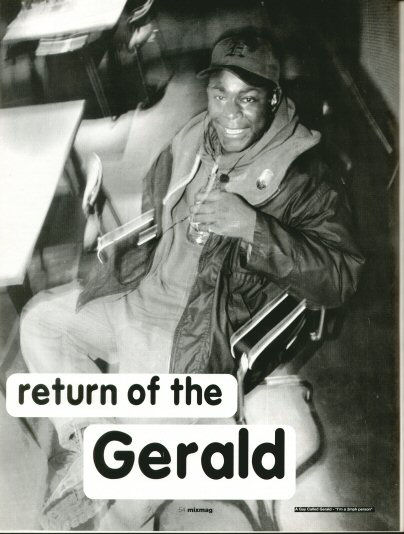

With 'Voodoo Ray' A Guy Called Gerald defined British acid house. With '28-Gun Bad Boy' he lit the fuse that became jungle. With his new album 'Black Secret Technology' he is about to blow up. This isn't just a story of one man, it's a story of British dance music and jungle, of council estates, of drum machines and dreams. Words: Bethan Cole Picture: Simon King GERALD Simpson is smiling, and you can't help smiling with him. It's a crisp December day in Manchester yet like the lyrics of his evocative breakbeat jewel 'Finley's Rainbow', the sun is shining, the sky is bright blue and the clouds are sky high. For a split second in the expansive Northern light, everything is clear. A Guy Called Gerald. You'll know him because of 'Voodoo Ray', the underground-overground apex of British acid house. Our very own 'Strings Of Life'. He was that everyday bloke from Hulme who knocked up one of the most important records of the 80s on two keyboards, a drum machine and a tape recorder. As time elapsed, however, you didn't know him. He also co-wrote 'Pacific State' (but back then no one knew). He signed to Sony. He went around the world. Recorded with Derrick May and Joe Smooth. Then he came back. Submerged himself in the studio for a few years and made another record, 1991's '28-Gun Bad Boy'. It was in many ways as pivotal as 'Voodoo Ray'. A breakbeat track, that, like Goldie's 'Angel' and 'Terminator' signalled the kick of something as original, revolutionary and earth shattering as 'Voodoo Ray' had done three years before. What it all adds up to is that Gerald never really went away. He may have flashed out of the mainframe for a few seconds. But in real time he was evolving and nurturing the sound we now know as jungle. Now his new album 'Black Secret Technology' has arrived, Gerald is back to collect his dues. And his story, like Goldie's, may give more clues than any other to how jungle, this truly British sound, came to be. GERALD'S tale is also very much a Manchester tale. He was born in Moss Side in 1967. His parents - father a rubber moulder in a nearby Dunlop factory and mother a nurse, met in the city after arriving from Jamaica in the early 60s. When Gerald was five, they split up and for three years mother and children left the city, returning to Rushholme in Manchester when Gerald was eight. But after being uprooted he found it difficult to settle back down to school, spending more and more time getting into trouble with his brother. "They put us in a home because I wouldn't attend school. We were terrorists and I don't mean like little things. We used to rob cars and set fire to things," he recalls. Afternoons in the home were free and whilst others sat in front of the TV, Gerald started getting into music and jazz dance. He set up a sound system in his mum's attic with his brother and some friends. "We had two 18" speakers, on top of that we had a pair of 15" speakers, on top of them we had a pair of 12" speakers and on top of them airhorns, There was an amp, decks and the records I used to play. Everything was stolen. Even the wood for the speakers was robbed from a building site." All this time he was absorbing the experimental vein of black music that precursed electro. Listening to Mike Shaft on Piccadilly Radio he would tape the jazz breaks dropped inbetween the relentless groove of funk and Northern Soul. He started combing Manchester's record shops to find albums by jazz funksters Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea, fascinated by their avant-garde fusion of jazz and rock, drawn to the tense, militant edges of 70s syncopation. "Chick Corea was the first person I heard playing electronic synthesisers and stuff," he explains, still rapt with fascination. "I was so intensely into it, all his stuff, I know it note for note." WE'RE chatting over a few beers in Manchester's Isobar, a post-Manto, post-Dry, pre-club drinking spot where Gerald spins jungle every Thursday. He's talking about electro now. How he bought a little Roland machine and started scratching with it in the early 80s. How Greg Wilson's DJ sets at Legends turned him on to a harder electronic sound that was one step on from funk and soul. Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, Weather Report, Lonnie Liston Smith; somewhere along the line their jazz fusion sound struck a chord in today's jungle originators. 4 Hero, Roni Size, Gerald: they've all overtly or subconsciously touched drum n' bass with a sense of 70s/80s avant funk. Whether it's Roni Size's wholesale looping of Lonnie Liston Smith's 'Expansions' on 'It's A Jazz Thing' or the echoes of silky-smooth Patrice Rushen on 4 Hero's 'Universal Love', we're dealing with a music deeply indebted in spirit and form to the proto electro sound. "I don't think the jungle thing started three years ago," asserts Gerald. "It was started by the generation I'm from, young blacks that were born over here, who listened to music from other countries, brought that in, tried to imitate it and then finally matured to a level where we could actually do something positive with everything that's been fed to us. It's like a movement." During the mid-80s Gerald began to spend more and more time creating his own version of the rap tracks and Chicago sounds he was listening to and buying. He and Nicky Lovett (MC Tunes) would jam with Carson and Anderson (who later became The Rap Assassins) on the sound system still in his bedroom at home. Sundays were hip hop only days. The rest of the week Gerald would mess around on the 303 he had picked up and heard on Ice T records. One day he went into a record shop with a few tapes he'd made up and the DJ gave them to Stu Allan, the Piccadilly radio jock, who played one on his show. "I was really chuffed. I took it more seriously after that." WHEN Gerald made 'Voodoo Ray', he was living in a squat, conducting phone interviews from a call box and still working in MacDonalds. You'd see him walking around Hulme on TV documentaries. The classic stuff of Manchester mythology. So what happened after? He worked with 808 State (in their early incarnation), helping to shape their sound on tracks like 'Pacific State', He signed to Sony in 1990 for two albums and toured the US and Japan. He linked up to a world network of electronic musicians and reconnected himself to the raw groove of Chicago house. He recorded with Derrick May - who remixed 'Automanik', the title track from his first album for Sony. Found the true roots and inspiration of his mid-80s house work in the dark, throbbing warehouses of Chicago. Did some cuts for Carl Craig and Damon Booker's label Retroactive. And then, at around the same time that Frankie Bones was mashing house with breakbeat on the 'Bones Breaks' tracks, Gerald did a PA in New York, floating 'Voodoo Ray' over a tearing drum and bass percussive. "I worked on that sound," he says, explaining how it had captured his imagination. "I'd done it before, a track I did while I was doing demos for CBS called 'Specific Hate'... it was actually released." GERALD returned to Manchester, fired up about the progressive new drum programs he was using. Simultaneous to producing 'High Life Low Profile', a second album for Sony, he created '28-Gun Bad Boy'. It was choppy, raw, snare-dominated and fierce, completely at odds to the Chicago-inspired material produced for Sony (which he kept recording as Ricky Rouge later on). He'd go down to Rage in London every Thursday (where he met Goldie), absorb the vital energy of Fabio and Grooverider's futuristic sonic hardcore and return to Manchester, channelling it all into tracks for a new label of his own: Juice Box. "'28-Gun Bad Boy' was the record of someone who'd gone around the world, only to come around the block again and find it all here - in Britain," says Goldie now of this pivotal track. All the elements of a fresh musical genre were tightly wrapped up in those first Juice Box releases. Rudeboy MC chatter (courtesy of old collaborator MC Tunes), airy electronic chords, Blaxploitation riffs and peppered, machine-gun assaults. Now the world has caught up with Gerald and the highvelocity ragga-breakbeat of bad-boy has hit the charts via General Levy and Shy FX & UK Apachi, Gerald is shooting off into the millennium, making drum and bass cuts that have moved beyond brutality to an aural promised land - divinely melodic and rhythmically deviant. You can hear the astounding culmination of this on 'Black Secret Technology', Gerald's new album. Experimental yet aesthetic, it articulates the rush of urban life and the naive emotional release that keeps us human so eloquently, so poignantly that you'll never want to take it off your stereo. 'Energy', one of many collaborations with Goldie and released as a single under the name The Two G's, marks the meeting of the two most influential producers on the scene today. Like 'Voodoo Rage' - a glorious retake on the original - it glides, assaults and rolls all at once. "It's funny because Goldie is like a 50mph person and I'm sort of more like your 2mph person. It was ironic that it was called 'Energy' because it's like a negative charge and a positive charge, two opposites coming together to create energy." But if there's one striking example of Gerald's genius on 'Black Secret Technology' it's 'Finley's Rainbow', a vocal track carried by strings which curve off over the ends of the earth and delicate plucked harmonies. And it's appropriate then, that amongst the experimental expanse and crystal shards of drum and bass on this album there's a rainbow. A glimmering arc spanning a lifetime of futurist fusions of the dancefloor. And. as in all the best myths and stories. you can be quite sure about what lies at the end of this rainbow. 'Black Secret Technology' is out end of February. The Two G's 'Energy' is out now on Juice Box [Author: Mixmag] |

|