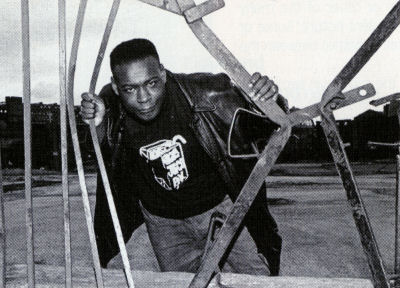

| Bush Scientist | |

|

The Wire Issue 131 January 1995 Page: 16 |

How A Guy Called Gerald is remapping the urban Jungle It's appropriate that Gerald Simpson, aka A Guy Called Gerald, has called his new album Black Secret Technology because this defines the last four years of Jungle perfectly. 'Black' in the sense of the music as a cult of 12" vinyl mixology in the age of the silver CD. 'Black' again, in the sense that, like James Brown's transformation of R&B into the cold machine of funk or Miles Davis's electrification of jazz, it's the latest example of the polyrhythmic aesthetics of black electronics. 'Secret' in the sense that it's a mental rewiring of taste and habit (mirroring the 91/92 exit from Britrap of so many Junglists) which has led to the emergence of a brilliant generation of aural hackers who have realised there's no bass in cyberspace and so have invented their own instead. And 'Technology'? Maybe I should let Gerald get a word in here: "First I'll put a load of drum loops down, chop bits and pieces of them, reverse bits of them. I'll take a snare, stretch it and take the middle bit out of that. On top of that I'll layer it with little bits of 808 drum machine, 727 percussion, little bits of 909. Then I'll do a riff on tape and build something to go with that riff. While that's working, I'll take the original riff away, work on the riff I've just made, then take that away until I'm left with the first and the last riff. It's seeing what fits and what doesn't." What fits and what doesn't: it could be the maxim for the singles Gerald has released over the last two years. Tracks such as "Nazinji Zaka" - a title lifted from a South African anti-military song - in which slippery thickets of fugitive, barely locatable rhythms and queasy post-Cabaret Voltaire synths heave and lurch like the sandworm from Dune. Or the lavishly widescreen cibaBollywood orchestrations of his remixes of Suns Of Arqa's "Govinda's Dream". Or "Finley's Rainbow", in which a whippet-fast pizzicato string section lashes the breakbeats as they skid and bank, nip and turn, until the most forlorn roots voice starts to sing, away from the mic and out of the window: "I want you to know right now/That I'm a rainbow" Where fellow Jungle producers such as the great Hyper On Experience or Dillinja produce fiercely militant beats and D'Cruze or Blame And Justice suffuse you in a feather drift of drum patterns which caress like fingertips, A Guy Called Gerald, like 4-Hero, bends and curves his drumtrips into intricately non-aligned tempos, squishy-scratchy scribbles. All the melody which the above experimental singles repel goes into the songs Gerald records and sings as Ricky Rouge: Nu Groove-y Garage and sparse House tracks such as "Song For Everyman" and "When You Took My Life" made in the spirit of forgotten Chicago House figures such as Joe Smooth. Such a reference reminds you how far back Gerald Simpson goes. When "Voodoo Ray" and 808 State's "Pacific State", both written by a Derrick May/Return To Forever-loving 22 year old from Oldham, were zeitgeist hits in the "Fight The Power"/"Back To Life"/"Big Fun" summer of 1989, The Stone Roses and 'Madchester' were appearing on Time magazine front covers. Gerald even remixed The Roses' "Fools Gold" (the ultimate 'Madchester' track), had it rejected as 'too dancey', only to see bootlegs selling subsequently in New York for $50. -Voodoo Ray" was sort of an attempt to do what the Detroit guys [ie Gerald's early Techno heroes: May, Juan Atkins, Carl Craig] were doing but it came out wrong and got into the charts instead," he laughs. While The Stone Roses grew beards for the next half decade, Gerald signed what turned out to be a disastrous deal with Sony, who, among other things, refused to release the Chicago House-inspired High Life Low Profile, an album he'd spent a year working on. In fact Gerald's had problems (with 808 State, with his first label, the Liverpool independent Rham, with distribution) throughout his career, something that explains a reticence that periodically surfaces throughout his conversation. "Jungle was beginning to happen and I wanted to be a part of it," he recalls, his face brightening quickly. "I set up Juice Box [his own label] in 91 and started making tracks, but people were after me, people who saw I had something going on and wanted a piece of it." You can hear Madchester collapsing in on itself on early Juice Box singles such as "Digital Badboy" and "Like A Drug". "A lot of people out there are wondering why I started doing this type of music," Gerald wrote on the back of 28 Gun Badboy, the 1993 compilation of those raw tracks, so brutally unpacific in their ruffness. "The reason is I'm living in a violent environment so it reflects the kind of music I make." Flick back to the first compilations of Detroit Techno and you'll find quotations from Derrick May and others to the same effect: Techno, they were saying, is what happens when an infrastructure collapses and the ruins of late capital's imaginary landscapes are traced in analogue circuits which have to break with an oral tradition no longer able to mediate new songs of sorrow. And as gangstas and badmen stalked the smoking cinders of the former Dance Capital Of The World, Gerald's early tracks, exhilaratingly vengeful, full of Blaxploitation flashpoints, were the only music to capture the aftermath of the Altered State that was Madchester. "The kind of music I'm doing now is shunned in Manchester," he says angrily. "There're no clubs that'll play it because they're all paranoid; they think there'll be gun business. You might as well call Manchester a Jungle free zone. But if you go to a dance you'll see the badboys jumping up and shocking out. They don't want to know about trouble. They just wanna know about b-lines and rhythms." Black Secret Technology is released later this month on Juice Box. [Author: KODWO ESHUN] |

|