| Break expectations | |

|

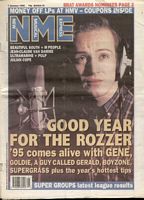

NME 7th January 1995 Page: 10 |

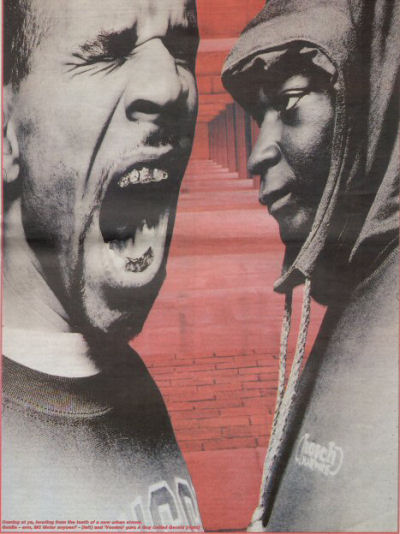

One is the brightest hope of the breakbeat scene, the man who put the gall into jungle with his fusion of soul, jazz and hardcore. The other is the rave legend who vanished, swallowed by an indifferent biz but back rising again, perhaps unstoppably. GOLDIE and A GUY CALLED GERALD trap ROGER MORTON in a London high-rise block. Wide-angle view: VINCENT McDONALD You wanna get a perspective; you have to get up high. You want to look down into the guts of the inner city; you have to shudder up 18 floors in a clanking dysfunctional lift, rubbing shoulders with the indominatable tower block Grannies of London's societal margins. Turn right and two flats along there's a maniac-proof metal grid protecting a front door and on the other side, one hardcore lump of muscled canine in a studded collar, and two men who are in the process of re-spraying the urban musical view. It's mid-morning round at Goldie's concrete perch. The man with the metal teeth is still getting his Stussy shirt on and cussing the dog. His Manchester mate and one-off musical collaborator (A Guy Called) Gerald sits on the sofa quietly sipping coffee, hemmed in on three walls by scores of pinned up baseball caps and a set of Goldie's psychoactively super real graffiti art canvases. It is, however, the fourth wall of the flat that concerns Goldie and Gerald the most. The window at the end of Goldie's living room looks out over a cityscape, which the two of them are helping to re-define. At the start of the '90s, as rave culture began to flag, street level music was left in a schizoid state. Clubland fragmented into insular sub-genres, hippy dance legged it to the mysterious east and ragga and hip-hop kept looking to their roots abroad. There was no obvious contender for a home grown grassroots music, which meshed with the harsher realities of post-utopian urban living. But there was hardcore UK breakbeat. THE RISE of 'jungle' drum'n'bass culture has been one of those re-connecting jolts, which takes place every time music noodles off into safe, self-indulgent irrelevancy. Against a background of drug use gone ugly and technology gone exponential, hardcore has gradually mutated into the most environmentally plugged-in current form. A freaky and genuinely multi-cultural genetic fusing of rave, hip-hop and reggae, it patrols the streets below Goldie’s window like some tooled-up, armour-played survivor of the musical gang wars of recent years – booming, speedy spliff music for scary, uneasy living. The years of hardcore being spat upon as cheap, lowbrow sweaty rave music, while a tight scene of DJs, club runners, pirate stations, indie labels and obscure studio-heads kept the faith, have made the OJs (original junglists) defensive. But the passion, which caused so much in fighting when jungle (and outsider ragga man General Levy) hit the media last year, is also responsible for its pressured evolutionary curve. The raw mania of old school Mickey Mouse hardcore is now just part of a wide genre which is gobbling up future-soul or spitting out (so-called) ambient jungle at a. scary rate. And Goldie and Gerald are two of the most graceful and far-sighted operators currently mapping out the future. The airbrushed assault of Goldie’s Metalheadz project swept the jungle board last year. Gerald, with his late '80s 'Voodoo Ray' Manc roots and a recent spate of 24-carat 12"s, is something of a born again breakbeat hero. So in the aftermath of their collaboration on a single 'Energy/The Reno', the two G's look down on the squabbling metropolis and survey the scene past and present.  Goldie: "I remember Gerald from before he remembers me because he’s like our hero. I remember hearing ‘Voodoo Ray’ in the background and my mates were like dropping acid and I was like ‘What’s all this?’ The next encounter was hearing Fabio play his stuff at Heaven, when breakbeat first kind of came in. "For me it meant that it had gone full circle because it was people like' Fabio who were playing Gerald in early acid: days. In a way nothing's really changed, because they're still playing cutting edge beats. It's just the trendy DJ circuit decided that breakbeat was the bastard child of house and disowned it because it was crusty and dirty and came from the street. No one wanted to be in that clique. But we were already in it and it was good. It was like punk, it was rebellious." Gerald: "In Manchester there were a lot of people saying it was 'rave music’ and they were getting out of that because after things like 'Charly' for them it was like 'sweaty rave', but I knew that there was something there and I just kept me head down and kept at it. And then one day I got a phone call from Goldie saying come down. I didn't know anything because I was up in Manchester. I was summoned down to Rage at Heaven." Goldie: "The thing is at the point when we were calling things 'jungle', breakbeat was developing. It's the same as graffiti. When it began it was tags and just people getting up and making a rowdy mess, and the general public thinking it was shit." Gerald: "I think people are realising what it is now. I went out to a bar last night and they were mixing breakbeats with jazz and it was working. I was watching the reaction and it was the kind of people that you'd get in Camden, like really kind of hippy. A couple of months ago they would have been confused at what was going on, because it takes a while for them to get used to the new format." Goldie: "Yeah, well let's face it, it is the new format for the '90s, no matter what anybody says. There's all different flavours involved, it's not just one thing, it can be reggae, soul, hip-hop whatever. The barriers are down, the music can have as many different flavours as there are, and it can be made by so many different people. "It's like when DJ Peshay first started making stuff people thought ‘Fucking hell' and then when they saw him they couldn't believe he was a fat white geezer from out in the sticks. It's just reflecting the society we live in, a multi-cultural society. I mean if you never went out raving I don't see how you can appreciate it fully now. We appreciate the history of it.” Gerald: "I think the major labels should be a bit embarrassed because it’s all happened under their noses. Going back two years, I remember going to a record company and playing them some things and they were like, 'Well, it’s a bit ravey, can’t you slow it down and put a different vocal on that?’”  I mean the press jumped on the Levy thing because it was a face to put to the music, but you can't mould it into a pop thing. "Jungle has to be spelled out. It's the subculture of this country and it's the new culture and people don't understand it We don't want to make the same mistakes that LA made and let the crack situation take over the youth culture. Here we're aware of the-social decline and I think it's not too late for us to help that situation. "People tried to say this music was crack music. The biggest fucking wanker and I'm going to quote the fucker, mate, is Malcolm McLaren, on MTV he turned round and said, 'Yeah, this breakbeat music, it's music for crack heads'. I thought, 'This is the geezer who milked hip-hop to the f-in' bone'. He didn't realise what he was talking about. "Somebody said to me the other day, 'Goldie, we've changed the youth culture of this country' and that's heavy shit that is. I had some kids come round from this youth centre last night, kids who were doing a project on jungle, and they're like kids who can't even go out and rave, butt hey get the tapes and whatever else, and I want to contribute to educating those kids." FOR A man educated in the school of biz hard knocks Gerald is unusually laid back. Perhaps he just knows that six years after 'Voodoo Ray' he's back on target. At 27, he's survived legal battles with 808 State (over who wrote 'Pacific State'), a mismatched spell on Sony resulting in a year's work on an unreleased album and protracted management problems to re-emerge as a respected figure with his own Juicebox label. His '28 Gun Bad Boy' single did the groundwork. Now; after successes with 'Finley's Rainbow' and a remix of Suns Of Arqa's 'Govinda's Dream' he's about to release a future breakbeat album 'Black Secret Technology (including 'Voodoo Ray' remixed as 'Voodoo Rage') which-should confirm his musical renaissance. "I just found that the best way for me to work was to just put stuff out meself," he says. "That way no-one was doing shady deals behind me back and if I wasn’t getting paid I just had to go down there with a baseball bat and get paid. After being on Sony and being told what to do, I just thought, ‘Well, I’ll go for it and do what I want, play at the tempo and use the samples I want’. Things like ’28 Gun Bad Boy’ were sort of saying ‘F--- you’ to Sony in a way. “I wasn’t really into the European stuff that was coming out. The Belgians and German ‘Make Some Noise!’ thing was a bit too cold. I was listening to everything from street soul to ‘Papua New Guinea’, the really early breakbeat styles. With ‘Black Secret Technology’, there’s a lot of inspiration there from people like 4 Hero and Goldie as well. It’s weird because that sort of come out of what I was doing years ago and they took it to a new phase. So I’m being inspired by something that was inspired what I was doing years ago.” Integrating the manic shuffle of jungle with Gerald's cyber head visions, ‘Black Secret Technology’ is the future seen through a glass darkly. It's probably not incidental that he recently witnessed a body being dragged out of the canal outside his studio. "It's really creepy round where the studio is," he says. Too creepy in fact. Having been burgled twice in the space of two weeks, Gerald's resolved to move to London, hoping to find a more “positive” locale. "I want to try and push what I'm doing and what everyone's doing over to the States," he says. "I think in certain areas people listen to music over there. I mean look at jazz This scene's not as old as that, and there's so many people that gave up their lives for jazz so you can't really compare this scene with that. But it's getting that way.” AT 29 Goldie's the newcomer with a murky past. But in the two years since his '92 'Killermuffin' EP debut; he's proved himself to be one of the leading lights of advanced jungle. His three releases as Metalheads -'Terminator', 'Angel' and the hit 'Inner City Life' - took breakbeat to new levels of string soaked, time-stretched atmospheric sophistication. 'Timeless', his epic blues for the '90s, is 22 minutes long and a work of near genius. His re-mixes, including Massive's 'Helicopter Tune', and 'Ice Cube's 'Body Bag' have been widely acclaimed and with an album on London Records set for '95 and charisma like a knuckle duster he's the underground golden boy of the next year. A foster home kid from Wolverhampton, he spent the '80s, steeped in hip-hop, living a full-on BBoy lifestyle and making a name for himself as a classy graffiti artist. With his black Merc, mean dog, Stussy gear and gold teeth he's equipped with all the accoutrements of a B-Boy hard man. But Metalheads music eschews the battering ram tactics of mental jungle in favour of trippy, mind-bending atmospheres, complex breaks and sweet soul vocals (most effectively from Urban Cookie Collective's Diane Charlemagne). In a scene, which has inherited much of the bad boy stance of gangsta and ragga along with the breaks and the basslines, Goldie's well positioned to take an overview. Having lived in Miami in the late '80s, he's done the criminally minded thing and popped out the other side. Prize open his jaws and there's the heart of a community spokesperson and street philosopher beating away at 160 bpm. "I think graffiti stopped me getting into trouble," he says. "I put a lot of time into the community side of it so it was kind of a cool situation was trying to do a bit of this and that but I was never a successful thief because I'd always get caught. I remember we did this big fuckin' warehouse job on these sheepskins, man, and I was last up the rope and all that bollocks. I'd always fumble it. We'd try and mug old ladies and I'd feel guilty at the last minute. I'd end up more or less escorting her across the road. Maybe it was the artistic streak in me that wouldn't allow me to do that. “If you live in a place like Miami, you get to understand the real values of people’s lives. Like when I see all these bullshit fucking people over here trying to provoke trouble and wanting to be bad. When I first came back from Miami, I was on that whole drug thing, fucking about. I’ve seen more fuckin’ kilos than any motherfucker’s had hot dinners. And it’s like, ‘Why the fuck did I play that role?’ Because it’s not cool. “You know I’ve got fucking scars, I’ve got wounds man, and fucking pickaxed here and stabbed there and nearly lost my hand one time because there’s always some bigger badder man. When I went to Miami, that was the biggest wake up for me because I had fucking 14-year olds trying to jack me outside the flea market, and I’d have to fuckin’ reach for my things. But it’s the reality of it all that you just learn to adapt to that lifestyle. “But then you think if I hadn’t been there, would I have learned as much as I’ve learned. If I can come out the other side with a bit of fucking sense, if the music’s able to chill things out, like the hip-hop culture certainly brought down those barriers between gangs, and I hope that this drum and bass culture has done the same thing for this country. It’s brought a lot of people together who would not necessarily be together. Because the Government would quite well want us to obliterate our numbers and consume ourselves on crack and consume our own fucking shit and die. “People go to me, ‘Oh I didn’t like that tune because it’s moody’ but that’s what I’m feeling there and then. The only reason it scares people is because it’s real. I make real music that reflects the real ‘90s. And I guess some people can’t deal with that. “They were all saying, ‘This isn’t music’ and now they’re all eating their words because they understand that this music is dangerous. It’s urban fucking music: ‘New Urban Blues’. And there’s no rules now. The equipment’s gone AWOL. We’ve got a reign on the big studios man. We’re freaking them out and that’s the whole point. You have to understand that this was a culture that was developing and you can’t oppress a youth culture. That’s what happened here. But people oppress this music and it’ll be the most powerful music by the end of the decade.” YOU HEARD the man. The streets of London? Manchester? Birmingham? Paved with Goldie, patrolled by Gerald and lit up by future-breakbeats til daybreak 2000 at least. [Author: ROGER MORTON, Photos: VINCENT MCDONALD] |

|