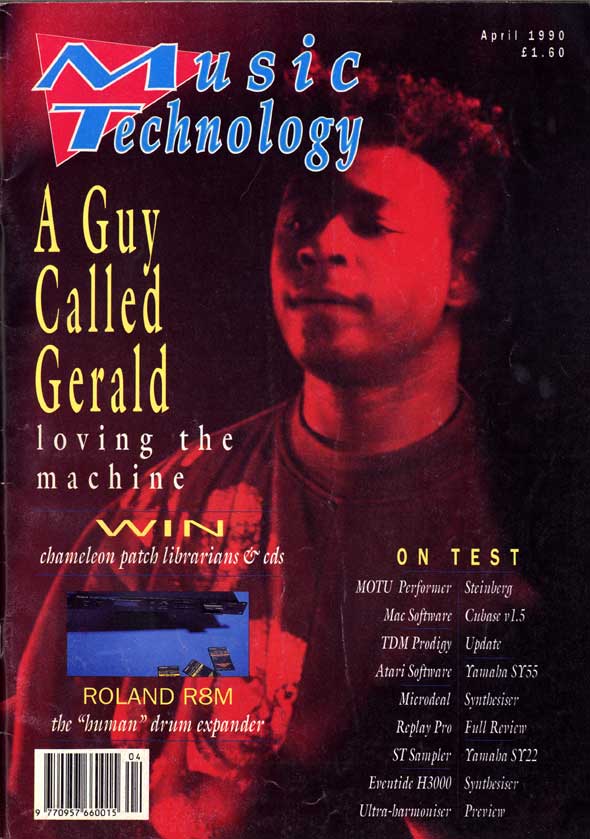

| A Guy Called Gerald - Voodoo Chile | |

|

Music Technology April 1990 Page: 50 |

A GUY CALLED GERALD'S EYES LIGHT UP as he recalls countless hours spent making music in the attic of his parents' house when he was a teenager. "I had an 18" speaker each side of the room, and 15" speakers on top of those. There was a mixer with a turntable at each side in the middle of the room, then an 808, a 303, an SH101 and a little tape recorder. Sometimes I'd program the 101 so you couldn't hear the bass but you could feel it; the floor used to shake and the windows would rattle... The Ruthless Rap Assassins used to come round and we'd just jam. We used to call it The Attic Studio. "But those days are ended now. I reckon they were the happiest days of my life. I had total power coming from the speakers, and I could make any sound I wanted over these records and be mixing them in at the same time. Then I had to do the foolish thing and send my music to the radio stations, and get caught up in all this music business!" Still only 22 years old, Gerald Simpson has had to grow up quickly in the wide and often wicked world that exists outside his beloved studio. As a naive but talented youngster whose only interest lay in making music, he was ill prepared for the attentions of other people who were more interested in making money at his expense. "I'd do anything because I loved the music, and if there was any chance to get in the studio I'd take it", he admits, as we sit in his hotel room in Earls Court, London. Now with his own label, Subscape Records, and distribution through the mighty giant that is CBS Records, A Guy Called Gerald seems to be on top of things at last. He's recorded, mixed and cut his second album, the deep, brooding, atmospheric Automanikk, a more mature, accomplished and well-rounded affair than his hastily-conceived 1988 debut album Hot Lemonade. And the night previous to our meeting he played the first show of a 19-date UK tour which is set to take him the length and breadth of the country in almost the same number of days. Tonight he's playing at the University of London Union, and his tour manager puts in an appearance every now and then to remind him that he has to leave for the soundcheck soon. Gerald remains unperturbed. He's learned to relax, to stay unfazed by the demands of those around him. Later on we take a leisurely stroll through the backstreets of Earls Court as lensman Cumpsty searches out a suitable location to snap the pics, leaving a perplexed tour manager to wonder where the hell the star of the show has disappeared to. And Gerald is a star now, though his shy, quiet-spoken, self-effacing manner suggests that he's more at home in the shadows of the recording studio than the glare of public attention. There again, the massive success of his '88 single `Voodoo Ray', coupled with the subsequent financial problems that it led to, ensured that he was soon thrust into the spotlight, regardless of whether he wanted to be or not. Gerald made the fateful move from attic studio to professional studio after independent label Rham Records heard some of his music played on Manchester's Picadilly Radio. They quickly signed him up and put him into a local 16-track studio, Moonraker, with producers Chapter (Anif Cousins and Colin Thorpe). The resulting four-track EP included `Voodoo Ray', and the massive underground success of that track meant that he was soon in demand with other budding dance musicians. It also meant that it wasn't too long before Rham Records put Gerald back in the studio to record Hot Lemonade, even though he had yet to see any money from the single. Then Red Rhino, who handled distribution for Rham, went under. Gerald recalls: "With Rham Records it was like `Oh, by the way, the distributor's gone bust so you won't get any money off `Voodoo Ray', but get on with the album anyway'. And I still ran about for them. I was a sucker for that." Despite the fact that he wasn't getting any money from Rham and that the story was all over the music press, Gerald's friendly local dole office wouldn't have it that he wasn't getting paid. To make matters worse, he wasn't getting any money from 808 State for his part in their debut album Newbuild. "It was a bad time for me", he admits. "It was like 'Oh no, I'm fucked!'. I was getting messed around left, right and centre, and it was like I wouldn't be able to carry on living much longer if I didn't sort myself out. You can only love music so much, then if you're dead you can't hear it." Well, you can't argue with that. He never saw any money from the single or album, though recently he's won back the publishing on the album. The story according to Gerald of how he came to sign away the rights to 'Voodoo Ray' runs like this: "'Johnny Roadhouse', which is the secondhand gear shop in Manchester, had a TR727 drum machine for sale. I just had to have it. I thought 'Derrick May's got a 727, I've got to have a 727'. I signed away 'Voodoo Ray' for a hundred pounds so that I could get this drum machine. I had no idea that the record would be so big." Men have thrown away their careers for the love of a woman before now, but how many have done the same for the love of a drum machine? Of course it's easy to be wise after the event, and Gerald isn't the first musician, and probably won't be the last, to emerge older and wiser from his encounters with the sharp side of the record business. GERALD STARTED OUT IN THE EARLY '80S as a DJ playing electro records in the local youth clubs of his native Manchester. His introduction to the world of electronic musical instruments came in '83 when he chanced upon Roland's TR606 Drumatix and TB303 Bassline in A1 Music. "I remember thinking 'No way can all that sound be coming from those two little boxes'", he recalls with a gleam in his eye. However, it wasn't till '84 that he was able to buy them. "I felt as though I was going to take over the world with them. I used to mix in the 606 over records while I was DJing, and the audience thought it sounded excellent. Unfortunately my partner in DJing wanted us to concentrate on scratching techniques rather than muck around with drum machines, and when we fell short of money we had to sell it. That was definitely a mistake. I soon got out of the partnership to concentrate on making music." He took to working lengthy shifts at MacDonalds in Market Street, Manchester, in order to save up enough money to buy the equipment he wanted. In '85 he was able to buy a secondhand TR808 from Johnny Roadhouse. "It's such a reliable instrument, it's not given me any problems at all. I bought a whole load of Roland gear around this time. It was very difficult to know what pre-MIDI gear was compatible with what, so I guessed that Roland synthesisers would work with Roland drum machines. I bought a couple of SH101s and a CSQ600 sequencer to complement the 808 and the 303, and the setup worked very well." As he was getting into this gear, big changes were taking place in dance music. Chicago house and Detroit techno records were finding their way into Manchester on import. Gerald recalls the lengthy queues outside Spin Inn Records at ten o'clock on a Saturday morning as eager youngsters (himself included) clamoured for the new music. At the same time hip hop was "sort of sliding into samples and breakbeats, using other people's performances. I liked heavy electro, so it was 'bye bye hip hop, keep on with the breakbeats. Don't wear your records out, and I'll try not to wear my floppy disks out'." Gerald wasn't only interested in the heavy beat of the new dance music, however. "To many people, house music is just a beat to dance to, period. But it's a fallacy to believe that all a house track is is a 'four on the floor' drum beat and a couple of sequencers to pull it along. With my music, it's just as important to me to create a certain atmosphere within a track with unusual sounds as it is to create a danceable rhythm." With such an outlook it was hardly surprising that he gravitated towards techno: "Those guys came out with some sounds I'd never heard before. They've all got their own feel. Juan Atkins is more analogue, whereas Derrick May uses the DX100 - his sound is really sharp and aggressive. If you listen to the complexity of what he does... I reckon if you get into the machine, then you love it and you really learn to use it. When you love a machine enough you can get any sound you want out of it. I've spent years with my 808, 303 and 101, and I'll always be the master of them." And it was this setup which Gerald eventually used for the 'Voodoo Ray' EP, with the SH101 providing that curious almost-a-steel-drum bassline on 'Voodoo Ray' itself while the 303 did its acidic thing on the other three tracks. The whole EP cost only £800 to record. Gerald explains: "By having most of the programming for the tracks finished before entering the studio, we were able to keep the recording costs to an absolute minimum. We knew exactly what we wanted for the record and got on with it." However, the famous pseudo-Arabic vocal wail on 'Voodoo Ray' came about in the studio when Gerald encountered an Akai 5900 sampler for the first time. "That vocal sample was of a friend of mine who was working in the same studio as us. We thought it'd be a good idea to have a chant-like vocal on the record so we taped her improvising over the backing track that we'd devised. We found a fantastic section in her vocal which was almost Arabic in style, and sampled that for the main body of the song. By looping it and running certain sections of it backwards we ended up with an extraordinary, almost scat vocal line. We left the sound she had made drawing her breath at the beginning of the sample, which kept it sounding quite human even after all the looping." Gerald reveals that the actual sampled phrase 'Voodoo Ray' was lifted from a comedy record by Peter Cook. "I've got a huge collection of spoken word recordings which I sample tiny snippets from", he adds by way of further explanation. "I try to avoid using just the sound straight off the record, though. I often pitch-shift the samples or reverse them to come up with something new. What's the point of producing something that people have heard already?" Gerald is very clear about his attitude to sampling, and he's happy to expound on the subject. "Breakbeats are definitely out. There's got to be a better way of using samplers than just for stealing someone's record. People must use their imagination more. I could never understand why people felt that they had to go out and buy old funk records that were two or three decades old to sample them into a piece of gear that was made yesterday! Why sample off records even, when there's so much sound around us? "There's a certain band I know who were once sorting out a track in the studio. There was a section in the song where they wanted a peculiar crashing sound, but instead of using their synthesisers they got out a BBC sound effects record and sampled it. With all the equipment they had and with all their imagination they had to resort to that. I just stood there in disbelief. "If one of my records was sampled and used in a way that I liked I would take it as a compliment, in a way, because whoever sampled me would be stating on record that I came up with something which was better than anything he could do. But if someone bunged 'Voodoo Ray', say, into his track just because it's a house track and he thought he would gain credibility from it, that would annoy me. That would be stealing my music." Hmm. There's a fine distinction in there somewhere, but then the sampling issue seems to be all about where to draw the line between creativity and plagiarism. "When it comes down to it, if a musician was being creative I don't think he'd be using someone else's beat, he'd devise his own. It's like drawing a picture: what's the use of tracing someone else's picture if you can draw your own? Surely you'd be more satisfied if your work was entirely yours? "The problem stems from the fact that music nowadays is about making money, not about creating new kinds of music. Chart music has never produced anything new. Rather than trying to find their own style, many musicians are moulding their music for the charts before they even begin writing a track. Subconsciously they're thinking 'I'd better use this sample because it'll sound like so-and-so', and that's terrible. "If you copy someone's melody from a song and call it your own you'll probably end up in court. Why, then, can you do the same with samples and get away with it? In house and techno music the bassline and the drum part are the melody, in a sense, but they're unprotected by law." This argument was advanced by Blue Mountain Music, publishers of the M/A/R/R/S track 'Pump Up The Volume', when they threatened legal proceedings against Intersong, publishers of Sybil's 'My Love Is Guaranteed'. The gist of the case was that the backing track for Phil Harding's Red Ink remix of Sybil's track bore a striking similarity to the backing track of 'Pump Up The Volume'. Blue Mountain maintained that the bassline was the nearest thing to a melody on 'Pump Up The Volume' and it was permissible for the bassline to carry a melody (indeed, in classical music, and especially in pre-classical polyphonic music, the 'bassline' frequently carried a melody). But if sampling has become just another tool of commercialism, surely the same can be said about remixing. How can artists be expected to develop their own style and identity when their music gets used as a vehicle for the artistic impulses of the remixer? "I think there'd be a lot more music if there weren't so many remixes. That's why I've given up on that sort of game, I'm not doing any more for a while. The Stone Roses was the last one, and that didn't get released." NOWADAYS GERALD'S COLLECTION OF Roland gear runs to a TR808, TR909, TR727, TB303, MC202, two SH101s and a Jupiter 8, with an MPU101 for MIDI-to-CV conversion. A veritable Roland museum, except that these particular exhibits are still very much alive and kicking in Gerald's music. Although he now samples all his drum sounds into an Akai MPC60 for live work, this is more out of respect for his precious machines - which he always returns to for recording purposes. "Because I once used to carry all those instruments around so much, they're knocked about now", he explains, "so I didn't want to bring them out on the road again. Plus they went through the ordeal of being stolen recently, so I decided to leave them at home resting." Gerald's attachment to his old analogue gear is for more than just sentimental reasons. He knows it inside out, and for him that means he can get the best out of it. He's scornful of any suggestion that as hi-tech gear gets more sophisticated it can help people to become more creative. "It's ridiculous to think that your music will sound any better if you go out and buy or hire the latest keyboard. If you've got a feel for music and you know what you're trying to achieve, it doesn't matter what equipment you use, you can near enough get away with using anything. People tend to crave after better equipment when they don't know what they want from their music." If Gerald is beginning to sound like a fully paid up member of the technological luddite lobby, this is far from the case. He has no interest in turning back the technological clock. As he exclaims: "It's no use looking back; it's a waste of time companies like Roland spending millions on developing all these new instruments if no-one's going to use them." So come on Gerald, is there any new technology that you really want? "If anybody from Mai is reading this, sponsor me! I want an ADAM - I'll wear your T-shirt to bed, I'll wear it at every gig." Gerald's current home recording method consists of recording everything straight to his treasured Casio DA1 DAT recorder (which he carries with him everywhere, along with another electronic gadget, a Psion Organiser) through a "cheap and nasty" mixer, with a Yamaha SPX90 as his only effects processor. An Akai 5950 takes care of vocal samples, keyboard bits and pieces (like sampling a chord off the Jupiter 8 into the S950 and then playing it back from single notes) and sound effects. He currently uses the MPC60 for all his MIDI sequencing requirements. Originally he used the company's dedicated ASQ10 sequencer, which he purchased using money earned from remixing Cabaret Voltaire's track 'Hypnotised', but later part-exchanged it for the MPC60, which he describes as "a brilliant machine; you can do some really wacky things with it". Although it gets used for live work, he's now also thinking of using it for recording. He also has an Atari 1040ST sitting around doing nothing at home, and is aware of what programs like Notator and Cubase can do. "They're alright, but I'd rather use the MPC for sequencing", he announces. However, the new MIDI Manager page in Cubase, which allows software sliders and knobs to be configured onscreen for MIDI performance and SysEx edits, has him intrigued; the connection with his preferred analogue synth front-panels is not lost on him. Because discovering that unique, special sound has always been important to Gerald, presumably he is no fan of presets, no matter what machine they appear on. "I hate them", he confirms. "Nowadays you go into a shop or a studio, and the gear that's available gives you instantly interesting sounds at the touch of a button, but that sort of thing can make you lazy. It's far easier to press a button and get 'Super Dooper Bass Sound No.3' than it is to sort out exactly what sound would best suit your track. "It's rather like painting. If you're using a spray-can you're going to get harsh, straight, well-defined colours with no shades in between. But if you use a brush it's more manual, you have more control and that helps you to get what you want. The SH101 is rather like a painter's palette. You can see at a glance exactly what the components of your sound are and you can manipulate them instantly with its sliders. You have to make your sounds manually, and in this sense it's far more a performance instrument than a DX7 with all its presets. I'd like to see manufacturers making new instruments where you could manipulate sound manually in real time. I know it's asking a lot, but please?" GERALD AND HIS MUSIC HAVE GROWN out of the club scene rather than the traditional gigging circuit, so it comes as no surprise that his tour has been organised as a series of club nights - even where they take in traditional college venues (like the ULU). When the doors open at 10pm and Gerald isn't scheduled to go on till lam, you know this isn't a rock gig. The late hour hasn't deterred anyone from attending, though; when we arrive at the ULU around 11.30 there's a lengthy queue outside, and when we get inside the place is packed. Yep, it's sold out. Gerald is being supported on the tour by rappers the Ruthless Rap Assassins and Kiss AMC as well as guest DJs John DaSilva and The Jam MC. When the acts aren't onstage the DJs take over. Onstage Gerald controls the overall mix and uses the MPC60 to play the drum parts and to sequence the S950 and a Juno 106, with his Yamaha SPX90 plugged into the effects loop of the MPC60 for effecting the drums. He's joined onstage by keyboard player Rohan Heath, who's using a Roland W30 and a Kawai K1, plus a Korg 707 as a strap-on remote keyboard MIDI'd to the W30 so that he can occasionally step out from behind his rack and play a solo (in one case a screaming 'electric guitar' solo played using a W30 sample). Heath's role is to add live keyboard accompaniments and solos to Gerald's sequenced parts. They're joined by singer Viv Dixon (who also provides all the female vocals on the album), while Gerald himself takes the vocal spotlight for 'I Won't Give In', revealing himself to be the possessor of a husky, drawling and emotive voice, as he sings his song of defiance aimed at all those people who have tried to bring him down. Who says techno music is impersonal? Altogether they're onstage for around an hour, playing some ten songs including encores - one of which is a cheekily-included version of 'Pacific State', with Gerald vocalising the birdcalls and sax line. 'I shouldn't be doing this', he jokes, but nobody cares. The crowd are enjoying themselves. It's an effective set, with the mixture of live and sequenced parts gelling together well. Taking technology to the stage is nothing new to Gerald, as he's been doing it since his DJing days in the early '80s. At the ULU there were no apparent technological hiccups, but back at the interview earlier that day Gerald recalls with some amusement a show he did once at which the technology more than hiccupped - it had a seizure. "I was halfway through a track when the CSQ600 just stopped functioning. The audience must've thought it was some arty 'stop in the middle' because they applauded it. I think they eventually realised something had gone wrong when there was a five-minute interval between that track and the next while I was panicking trying to bring the sequencer back to life." With such a wealth of experience in a variety of aspects of the modern music scene, what lessons did he feel he had learnt? Gerald speaks slowly and thoughtfully: "I've learnt to keep myself to myself. I've learnt who my friends are, I've learnt to suss con merchants out, I've learnt to tell the difference between people who really love music and people who love music through their pockets. I've learnt to use a sequencer and sampler, and now I'm at the stage of learning how to engineer properly and how to use an SSL desk. I'm expanding from using my 808, 101 and 303 into a whole new world of studios." And one of the benefits of learning any lessons the hard way is the ability to pass on advice to those interested in pursuing similar aims... "I'd say get a keyboard and drum machine and learn them inside out. And before you do anything for anyone, get hold of a solicitor and sort out a contract. I know it costs money, but in the end it'll save you court costs. Don't be naive, because even if you just love making music and you're not really into making money, in the end you'll suffer because someone will take your music away from you." Sound words of advice from someone who really has learnt the hard way. [Authors: Simon Trask and Steven Hillier] |

|