1995 and the story begins

Many of my running trips abroad had been with other members of the 100

km Association, including Geoff Oliver. Trips to Botswana for the Gabarone

Africa Championship100 km race, with safari visits afterwards had whetted my

appetite for Africa.

Perhaps the most famous ultra in the world is the Comrades

in South Africa, run each year, but in different directions, between Pietermaritzburg

and Durban – a distance of about 90 km. The race was first run in 1921 as a

memorial event to the comrades who had not come back from the First World War.

Whilst there were just a handful in that first year, that race has grown and

grown to where it is today with up to 20,000 runners taking part. Its always

held on June 16th, which is a public holiday in South Africa and

it is the major activity out there on that day, with the road between start

and finish towns, closed to all but runners. Thousands line the route with picnics

and even more watch the daylong coverage on TV.

By 1995, apartheid was ended, (well theoretically ended anyway), and Nelson Mandela was running the new South African government. I would not have visited that country under the Nationalist apartheid regime, but now I was keen to run Comrades.

Any ultra runner worthy of the name, has Comrades down as an event to do. I

mentioned this to Geoff, to see whether he would like to come. Surprise, surprise,

not only did Geoff want to do Comrades, but knew Megan Perrin, an old family

friend living in Pietermaritzburg. Geoff had known Meg’s father through the

army, where they were both in the education side of things; Meg having been

a baby sitter for Geoff & his family in her younger days. She had been living

in South Africa for about 20 years, but was now in matrimonial difficulties.

Anyway, Geoff contacted her and yes, she would love to host us – which she did.

Meg was a nurse at the local St Anne’s hospital and she always helped out in

the medical tent at the end of Comrades for distressed and dehydrated runners,

(of which there were always many), so she knew the event well. She had no idea

though how much two ultra runners would eat and we found ourselves making trips

to the food stores to top up her larder and our internal ones

Geoff and I both had decent runs, with Geoff winning the over 60 section easily, with one of the fastest times ever recorded at just under 7 hours 30 mins. I was disappointed with my 8 hr 45 min, but would never get near that again. We stayed on for a week after the race, just long enough to whet my appetite even more.

As I mentioned, the race race changes direction each year and since 1996 was

to be the uphill run from Durban to Pietermaritzburg, I wanted to add the up

to my down - mad Comrades runners want have at least one of each, but Geoff

did not want to travel that far again, partly because he was distinctly dischuffed

at the lack of recognition for his 1995 feat. I wrote to Meg to ask if she could

find me a bed again, or if she could suggest anyone else – I was conscious that

she was now divorced and I did not want to be the source of any embarrassment

with friends and neighbours. She told me there was a spare bed at her house

and that of course I was welcome. During the course of my stay we found ourselves

gazing more and more at the other and realised that we were going to have to

be careful. She had been hurt by her recent marriage failure; I loved Jackie

back in England and I did not want to hurt her again, as I had done with other

affairs. I had been a naughty boy more than once.

We parted without even having kissed, but both longing for the other’s company. Neither of us could shut the thoughts out and it was not long before secret phone calls were being made. Almost before I knew what was happening, I was making excuses to go back to South Africa for other races in other parts of the country – with Meg also travelling to Cape Town or wherever the destination was. We fell passionately in love - yes, with me approaching 60 and Meg but 10 years younger. We did try to stay apart and stop phoning, but this was one of the cases you hear about, where ‘it is bigger than both of us’

Now it was 1998 and I was now approaching the toughest time of my life. I wanted

to spend the rest of my life with Meg, but to do that, I would have to hurt

Jackie, hurt my dear mam, leave all my family and friends, (including Bert),

and start anew. Eventually I knew that I had to take that plunge, because I

could never be happy staying in England, Meg would not be happy and Jackie would

find out sooner or later.

As I expected, Jackie was terribly hurt as was Mam – their hurt and accusing

looks will be with me now and forever. Jackie had done nothing wrong at all;

we had grown apart somewhat, but that was not only her fault; she did not deserve

what I did to her. However, we have stayed as friends, with the cancer helping

to close the rift and getting Meg and Jackie talking to each other.

The last day of October 1998 saw me bidding farewell to England and moving out to a new life in South Africa.

Move to South Africa

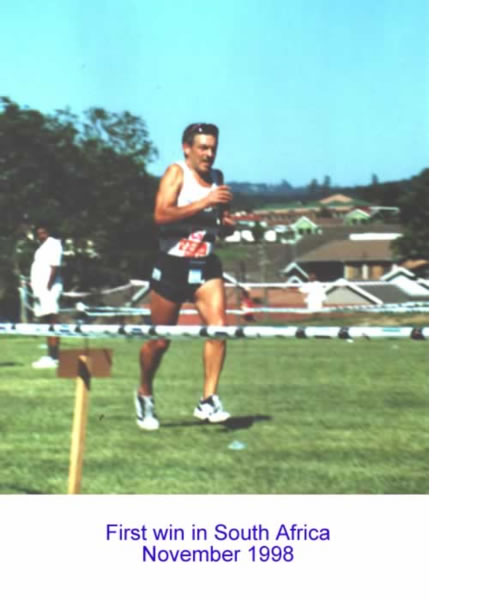

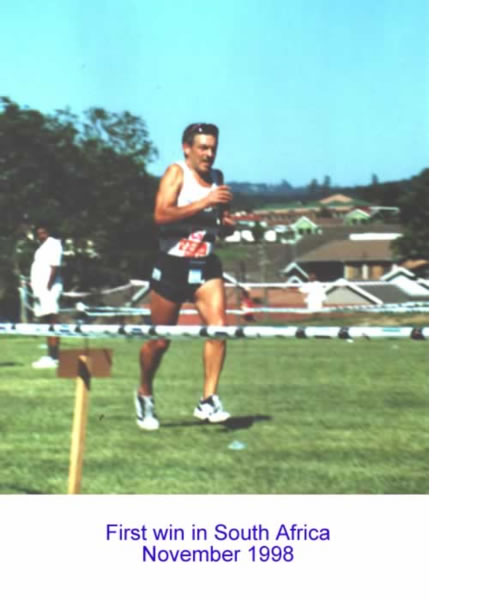

I was soon involved in one of the local running clubs, Collegians Harriers, opened my mouth with a query at the AGM and found myself elected as treasurer.

The heat of South

Africa and the hills on which Pietermaritzburg is built took some getting used

too, but running out there was tremendous with one of my favourite runs taking

me through Queen Elizabeth Park with zebra, vervet monkeys, impala and various

other buck. There were other scenic runs in the local forests, but I was warned

not to go on my own because of the danger of being attacked whether I had money

on me or not. I ignored those warnings – and nearly lost my life as a result.

The heat of South

Africa and the hills on which Pietermaritzburg is built took some getting used

too, but running out there was tremendous with one of my favourite runs taking

me through Queen Elizabeth Park with zebra, vervet monkeys, impala and various

other buck. There were other scenic runs in the local forests, but I was warned

not to go on my own because of the danger of being attacked whether I had money

on me or not. I ignored those warnings – and nearly lost my life as a result.

Running is such a hugely popular sport in South Africa with races being available most week-ends. I would be at most of these races, with Meg and other runners from Harriers, often winning my age group, (now over 60), and picking up a few small money prizes. They weren’t enough to even pay the fuel costs, but they were more than I had ever won before!

Collegian Harriers is one of the oldest clubs in South Africa. Harriers were

the organisers of the world famous Comrades

Marathon until it became so large that a separate Comrades

Marathon Association, (CMA), was formed, purely to organise the race

each year. There is still a very strong link between the CMA and Collegians.

We quickly made so many new friends from the vast running circle there to add to Meg’s friends built up over 20 years. Meg had left St Anne’s hospital since they could not offer her the part time employment which we wanted. We were travelling around the country at every opportunity. Wonderful scenery and game parks make South Africa a holiday destination without equal – and we were living one long holiday.

I often joked to Meg that the happiness which we had was beyond belief, but it would have to be paid for somehow, it was too much of a bonus. Life was bliss, but the upset was around the corner.

Cancer Strikes

In November 1999, just 13 months after we had started

our life together, we travelled for a holiday to Zimbabwe, just before the first

Robert Mugabe electoral fraud, which was to exacerbate the country’s economic

plunge. It was summer time and we were to see a lot of game, so malaria treatment

was a necessary precaution. Constipation began on that holiday, so much so that

I went to our GP friend on return to Pietermaritzburg. He could not believe

that there would be anything seriously wrong with the running man who was in

the local paper most week-ends. When he told us that constipation was a common

side effect of the anti-malaria treatment, we were happy with that explanation

and returned home.

January 2000 saw me winning an age group half marathon race again, despite the discomfort caused by constipation. It was getting worse, so back to the GP, who still could not believe there could be a real problem. There was no bleeding from the derriere and his exploration with the gloved hands found nothing. I had found that exploration so uncomfortable, that I put off his offer of a colonoscopy, simply because I too could not believe there was anything wrong and because I did not fancy the idea of a pipe up the bum. However, the silent killer was so far advanced that it would have made little difference. The constipation did not improve despite numerous laxatives; within a few days I was rushed as an emergency into St Anne’s Hospital in pain with a complete blockage of the colon.

Even at this stage, it was difficult to believe there was anything seriously

wrong – even Meg with 20 years nursing experience was fooled by the lack of

symptoms. There were lots of tears shed whilst we waited – we had only just

begun our love affair and it looked like being being thwarted. Graeme Reimers,

the surgeon called out that night, was forced to open me up, having first warned

us that there may be a cancerous growth and taking my permission to do what

he thought was necessary whilst he was in there and I was out for the count.

He had to take out six inches of colon with the obstructon, making a wonderful

job of fastening the two loose ends together, so that the colon functioned normally

again. We then had the agonising wait for two days whilst the biopsy revealed

that the cancer did appear to have spread - and that I would probably need chemotherapy.

The First Battle

Effect on Running

I was out of hospital in a record time of 4 days and starting the first gentle

jogging in another two weeks. March saw us making our, (I realise as I write

that I am using ‘we’ and ‘us’ – this is not an imperial ‘we’, just an acknowledgement

of Meg’s presence and care), first visit to our new oncologistist - Shane Cullis.

He gave an introductory explanation of the many different sorts of cancer, (I

do recall a figure of about 80 different types being mentioned), and then moved

on to colon cancer in particular. I would need chemotherapy to arrest and hopefully

remove the cancer cells; this would be done via a six month course of a drug

called 5FU infused into a vein for two days every two weeks. When I asked about

the likely effect on my running, he told me that if I was very lucky I might

be able to jog a few kilometres. I would not be able to do more. My response

is the title of this book!

It was amazing how much cancer seemed to be in the news. Before my harsh introduction, cancer was something which struck other people; my superman fitness would see I was ok, although the history of athletics shows cancer hits world champions, let alone me, just like anyone else – witness Lance Armstrong, Lillian Board, Geoff Boycott, Bobby Moore and a great ultra hero of mine, John Tarrant. From that introduction, the news always seemed to be carrying details of who else had been struck or of new research. I’ve chuckled many times at the research which says that regular exercise, a diet with little red meat, plenty of fish, fruit and vegetables topped up with dairy products would help stave off cancer – red wine too was an excellent protection. That was my diet described to perfection!

We were determined to carry on as before and the cancer was instructed to bugger off. I was not going to sit down and cry, "Why Me?". "Why not me?", was my reaction to that question, but what I did decide to do was take cancer on where I could and give it a fight

However, it was not as easy as that. I had Meg to contend with. As a nurse, she was used to paying full attention to what the doctors said, and I was carefully watched over as I ran further and further and further, eventually getting a gently run half marathon, (21km), under my belt. When I told Sean, the oncologist, he was not at all happy and tried to persuade me not to try anything longer. When I asked if I could try a full marathon, (42 km), his response was, "Oh, you shouldn’t", but I did taking it very steadily. Times were down on the pre chemo days but only by about ten minutes for the 42 km – I couldn’t care less about that, I was still able to run.

Have you noticed how I have now gone metric? For the non runners reading this, a half marathon is 13.1 miles or 21.1 kms; a standard marathon is 26.2 miles or 42.2 kms, whilst anything longer than that is a ultramarathon or ultra.

Just after this,

I was contacted by the PR section of St Anne’s Hospital to see if I knew of

any runners who had recovered from cancer, who might be able to run Comrades.

Big sponsorship for the Cancer Association of South Africa,

(CANSA), was being

offered. I didn’t know any such runners, but it did start the germ of an idea

in my mind – why not a runner who is still on chemotherapy? That was a story

which would interest the media and sponsors. I had not really considered doing

Comrades until then, but here was a opportunity too good to miss. Now I could

really give cancer a fight, using cancer itself as the means to raise funds

to use against it.

Just after this,

I was contacted by the PR section of St Anne’s Hospital to see if I knew of

any runners who had recovered from cancer, who might be able to run Comrades.

Big sponsorship for the Cancer Association of South Africa,

(CANSA), was being

offered. I didn’t know any such runners, but it did start the germ of an idea

in my mind – why not a runner who is still on chemotherapy? That was a story

which would interest the media and sponsors. I had not really considered doing

Comrades until then, but here was a opportunity too good to miss. Now I could

really give cancer a fight, using cancer itself as the means to raise funds

to use against it.

First of all I had to compromise with Meg that I would not put myself under

any pressure and promised to pull out of the race if I was struggling. Sean

had given up trying to tell me not to run – I even took him on board as a sponsor

together with many other doctors, the marvellous staff at St Anne’s, the chemo

company involved and my many running friends. Gradually I built up my distance

runs to the point where I had a 52 km run behind me. Then I was confident I

would be able to finish the course.

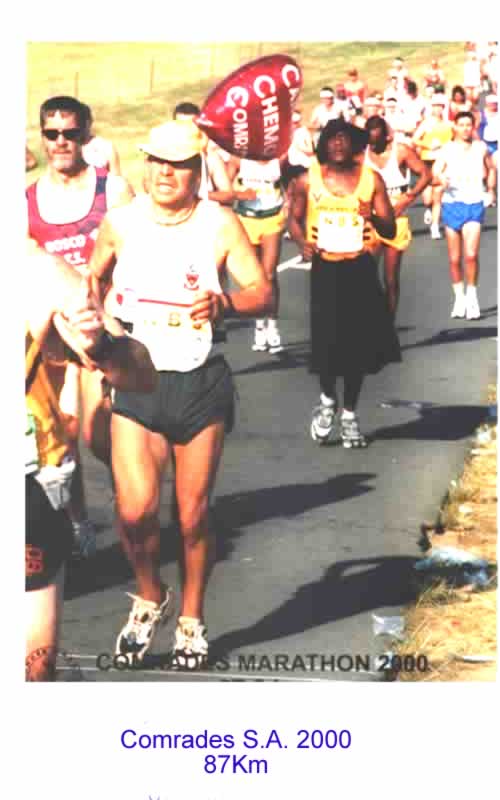

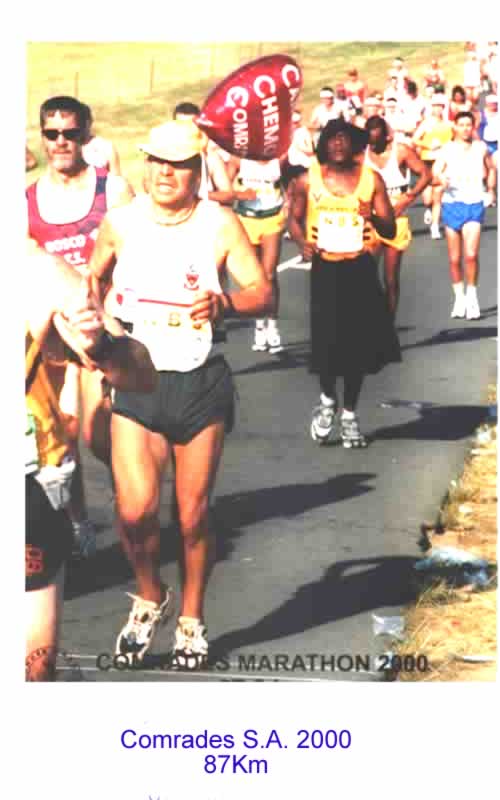

And so it proved, but not before I had become a mini celebrity in South Africa

with the story of a man daring to tackle Comrades

whilst still on chemo. All sponsors accepted that I might have to pull out before

the end, but that was an unnecessary condition. I took the run very easily,

deliberately being last over the start line to pick up the TV cameras, walking

frequently, chatting to the crowd and really enjoying the slower run. With no

pressure, it was so much more enjoyable than the earlier runs when I had the

self imposed pressure of aiming for a fast time. This run meant that I was the

first to run Comrades whilst on chemo, raising 50,000 rand in the process, but

more importantly, providing inspiration to cancer sufferers and their families,

with the message that life is still there to be lived, cancer and chemo cannot

stop that.

Three days later back on chemo, but with a Comrades finishers medal to boast

about.

Side Effects and Spin Offs

Side effects were few. The hair thinned and I was quite tired on the two days

in every two weeks when the chemo was infused, but other than that, it was almost

a non event. I carried on living and enjoying life much as before.

In many ways cancer was a blessing, since it concentrated the mind forcing

me to consider what was really important in my life and what was so much dross

to be discarded. The acquisition of money was no longer important, people were.

Which takes me to the effect of the shocking news of the cancer on family and

friends. After the colon operation, Meg had the job of phoning ex wife Jackie

with the shock news. Here were two women who both loved me, but who were, understandably,

not on speaking terms. Their mutual love for me has now brought them close together,

so that’s another thanks to cancer. My two sons shot out to South Africa as

soon as they could to see their old dad before he died – they could not believe

how well I looked. Seeing them, (and they have been another couple of times),

was also a ‘thanks cancer’ benefit.

The one person I desperately wanted to talk to was my mother. She had always

been so supportive and I really needed to hear a kind word from her. However,

I had hurt her terribly when I left Jackie to live in South Africa and she was

not ready to forgive me. I think she would have taken me back had she known

about the cancer, but she herself was now ill and degenerating slowly in a nursing

home. Her mind & tongue were a sharp as ever, but she was suffering from

mini strokes, each one leaving her a little more paralysed than before. She,

like Meg, was an experienced nurse and she knew full well what was happening

to her. Brother David, who saw her most days, did not want her to hear what

had happened to me fearing it would damage her further. After talking this over

with Jackie, I bowed to their joint wishes that I should say nothing. This lead

to a great deal of pain on several occasions when I phoned her - sometimes to

get the phone slammed down after another telling off. Tears were shed many times

with the pain and frustration.

Keeping things secret was not simple though. Plans had been made, before the

cancer struck, for Meg & I to do a house exchange holiday in April with

a family in Wallingford, near Oxford back in the UK. They would stay in our

house to see South Africa and we would use their house as a base to get around

friends and families in England; I say families, because much of Meg’s family

was also UK based. The house exchange was put on hold and lies had to be told

to mother about my having had an emergency stomach operation – but for a strangulated

hernia and not for cancer – which ruled out an April visit.

The six month chemotherapy course came to an end in August, with all the signs

being that the cancer had been completely removed and of course we were delighted.

After that fright, we were able to look forward to more happy years together

– or so we thought. Of course I knew there was chance it could recur, but regular

tests would keep an eye on that.

Meg & I were

not married, even though Jackie and I were now divorced – we did not really

see any need for any formalisation of our love, but the threat of my dying caused

a re-think, purely to ensure that she would receive a UK state pension as my

widow. So, we decided to formalise our relationship and where better than back

in the UK. We picked up on the delayed house exchange, spending three idyllic

weeks in lovely Wallingford – getting hitched at Didcot Registry Office on 20

September 2000. We kept everything quiet, having just Meg’s mother and brother

Glyn as the necessary witnesses. Jackie was not best pleased, but she understood

the reasoning.

Meg & I were

not married, even though Jackie and I were now divorced – we did not really

see any need for any formalisation of our love, but the threat of my dying caused

a re-think, purely to ensure that she would receive a UK state pension as my

widow. So, we decided to formalise our relationship and where better than back

in the UK. We picked up on the delayed house exchange, spending three idyllic

weeks in lovely Wallingford – getting hitched at Didcot Registry Office on 20

September 2000. We kept everything quiet, having just Meg’s mother and brother

Glyn as the necessary witnesses. Jackie was not best pleased, but she understood

the reasoning.

Our three weeks gave us time to call on just about all in those of our two

families who were in the UK, plus running friends such as Geoff Oliver and Ron

Hindley. It also gave me just the time to continue with my habit of fitting

in a race when on holiday. Actually I am telling an untruth – this time it was

three. I had already fitted in two marathons in the New Forest and at Nottingham.

There were so many old running friends with whom I could and did re-new acquaintance.

I had one UK race left to do though – the London to Brighton again. I knew it

would be hard to get over the line within the ten hour cut off, something which

had never been a problem in the past, but now I was still recovering from the

chemo’s slow down effect. Checking the watch all the way as I ran near the back

of the field, I knew it was going to be a close thing. At approximately one

mile from the finish, I had only eight minutes left – one mile in eight minutes

would normally be easily done, but here I had already run 54 miles. Head down

and go for it; as I approached the marina finish, I was met by Meg’s younger

son Ian and we sprinted in together. I crossed the line just 4 seconds outside

the cut-off time, thus officially being a non-finisher! I was disappointed that

the RRC could not bend it’s rules and award me a finisher’s medal – but them’s

the rules, so no real grumble

Next day it was back to South Africa and a second wedding celebration when

we hosted a reception at Collegians for almost 100 of our friends in and around

Pietermaritzburg. A night we will always remember. Then it was back to travelling

around South Africa and running too; winning age group awards again as we left

the cancer and chemo behind as a bad memory.

Leaving South Africa

The people in South Africa were so friendly, but their country was, and still

is, in the throes of shedding its apartheid views which are still strongly embedded,

particularly in the older folk, both black and white. So much was expected when

Nelson Mandela and the ANC finally took power, but the dreams for so many have

not been realised – they still don’t have a house or car, many do not even have

running water. Even more importantly, they do not have jobs, unemployment is

still so high. All this has meant a drift to crime for a minority of those who

are now free, in the sense that they have a vote, but still are ‘dirt poor’.

Its not just the poor blacks who are into law breaking though – it seems to

be a national sport to break the law, if there is little chance of being punished,

consequently corruption is still rife from Government level right down to the

ordinary man.

I had first hand experience of this at two levels, both connected with my running.

The first was where Collegians had grabbed me to be club treasurer when they

heard of my background, but I was soon to uncover the problems in money control.

Two separate members of the club committee had both been defrauding the club

in the previous year and tried to continue when I had taken control. I had never

met this sort of blatant dishonesty before, which was no more than theft from

friends. I could not believe what was before my eyes when I looked at the bank

statements – the rest of the committee were also shocked, but the miscreants

were both ejected, one after unsavoury legal action to get back what we could.

The second crime experience occurred when I was out for a Sunday morning training

run – ignoring the advice not to run alone. Three Zulu youths came out from

the long grass and started to run with me on what was a main road. I knew a

few Zulu phrases and chatted to them, but suddenly out came a long knife and

I was thrown to the floor. I was in my running gear and had no money, but they

took my bum-bag with radio attachment and my almost new shoes. I have little

doubt that I would have been killed, had the truck driver, who had just gone

past before the attack, not glanced in his mirror. He spotted what was happening

and raced back, resulting in the robbers vanishing whence they came – in the

long grass at the road side. The truck driver took me to the nearby local police

station, which would have taken only two minutes, but that is where I got my

next shock. They were interested only in taking a full statement, which must

have taken 30 minutes – not interested at all in going to the scene of the crime.

It was only weeks later when Meg was savaged by a bull mastiff. She was walking in one of the main roads near to where we lived while I had my morning run. The lady in the house opened her gates to drive out just as Meg walked past. The huge dog was out and on her in a flash with jaws breaking three ribs and leaving deep teeth marks and scars which are still there on the head, arms and back. The compensation she got was minimal, such is the importance of the ‘dog guard’ in white South Africa. It was not even put down, despite our insistence on a court case.

These two incidents were the straw that broke the camel’s back. Much though

we loved the South African life-style, the violence was getting worse. We lived

in a housing complex, the model of which is becoming increasingly popular, with

electrified wire all around the perimeter and security gates. It still did not

stop break ins, but at least they were made more difficult. The many break ins

did not just result in robberies – they were robberies with violence or murder,

to leave no witnesses. The people living in the complex, or in other houses,

might just have well been in prison. No-one dared venture out at night unless

in a car and even that was not safe, with car hi-jacking commonplace.

So we decided it was either back to England or try for Australia, where we

could have the weather benefits of South Africa, where the cost of living was

still way below that in the UK, although up on South Africa. A retirement visa

was applied for at the Australian High Commission in Pretoria, our declarations

giving full details of our assets and health. The Australians are strict on

who they let in - and this was to come home to us later – applicants must have

a large enough private pension not to be a burden on the Australian purse, they

may not work in Australia, they must have a clean police record, (there is a

joke there somewhere about the origin of Australia), and they must be in good

health. The cancer history was declared and a letter produced from Shane Cullis,

the oncologist.

To try to be certain that were making the right decision, we had arranged another

house exchange for three weeks in Bendigo in September. Just before we left,

it was time for another cancer check up. Three of the tests were ok, but the

tumour marker test file had been lost, meaning that would have to be repeated.

Off to Australia, to be most impressed with the friendliness and the safety.

No need to keep looking over your shoulder, no need to stay at home at night

and you were safe on the road. We were convinced – Australia for us.

I can still remember being in my office at home back in Pietermaritzburg, when

the phone call came from Shane Cullis. The missing tumour marker test had been

repeated and showed the marker going up, indicating that the cancer was back

in business. More tests to be certain, but the unwelcome guest was definitely

back. Not only was it back, but it had also set up home in the liver. Guess

what? Yes, more and stronger chemotherapy was called for. It was now late October,

so with Shane’s agreement, I put off the start of the chemo until the running

season was over in early December. Well, first things first after all. There

is very little running in the part of South Africa, where we lived, in December

and January because of the intense heat.

Now the question came again, would we be better off in the UK where at least

the costs of the chemotherapy would be covered, which is not the case in South

Africa, or do we still opt for Aussie. I had by then discovered that Australia

has a reciprocal health care agreement with the UK, under which citizens of

either country will be given treatment at no cost under the other country’s

health care system. I confirmed with the Australian Health Commission that my

chemotherapy costs would be covered. That confirmation and the fact that we

were not going to change plans and give in to cancer, meant we opted to continue

our plan to move to Australia. That was scheduled for early February, so I had

to make plans to continue the chemo once in Australia.

One of Meg’s Pietermaritzburg friends, Paula, had already left for Australia

about six months earlier. We were to stay with her for a few weeks when we arrived

in Australia, but first she provided a running doctor contact – also a South

African émigree. He recommended an oncologist in Melbourne, Michael Green,

who has been treating me ever since. The remarkable powers of e-mail allowed

me to set that up and put the two oncologist in touch with each other.

So it was just three lots of the new chemo, called Camptosar, which was given

intravenously like the 5FU had been, before leaving for Australia, but I must

just tell about the first one. We never did work out which injection had done

the trick, there are so many boosters, anti nausea etc injections which are

given before the chemo is pumped in. I was blessed with an almighty erection

which did not want to leave. Bending double and holding a bag in front managed

to cover it and it subsided, (without assistance), later in the day. I reported

it to the oncology staff and the nurses were of course delirious with laughter.

There was talk of a special cubicle being provided and admission by ticket only

for the next infusion. I was most disappointed though, the raising of the dead

did not happen again then or in any future session.

This time the more aggressive Camptosar oncology was hitting me harder.. I

was unable to eat properly on infusion days. For the first three days of the

cycle, it was as though there was a permanent post booze hang-over with nausea,

constipation and fatigue as problems. Day four or five would see me running

again, but the running was decidedly slower; it felt as if the brakes were on,

or like running having just finished a marathon

And on to Australia

The heat of South

Africa and the hills on which Pietermaritzburg is built took some getting used

too, but running out there was tremendous with one of my favourite runs taking

me through Queen Elizabeth Park with zebra, vervet monkeys, impala and various

other buck. There were other scenic runs in the local forests, but I was warned

not to go on my own because of the danger of being attacked whether I had money

on me or not. I ignored those warnings – and nearly lost my life as a result.

The heat of South

Africa and the hills on which Pietermaritzburg is built took some getting used

too, but running out there was tremendous with one of my favourite runs taking

me through Queen Elizabeth Park with zebra, vervet monkeys, impala and various

other buck. There were other scenic runs in the local forests, but I was warned

not to go on my own because of the danger of being attacked whether I had money

on me or not. I ignored those warnings – and nearly lost my life as a result. Just after this,

I was contacted by the PR section of St Anne’s Hospital to see if I knew of

any runners who had recovered from cancer, who might be able to run Comrades.

Big sponsorship for the Cancer Association of South Africa,

Just after this,

I was contacted by the PR section of St Anne’s Hospital to see if I knew of

any runners who had recovered from cancer, who might be able to run Comrades.

Big sponsorship for the Cancer Association of South Africa,

Meg & I were

not married, even though Jackie and I were now divorced – we did not really

see any need for any formalisation of our love, but the threat of my dying caused

a re-think, purely to ensure that she would receive a UK state pension as my

widow. So, we decided to formalise our relationship and where better than back

in the UK. We picked up on the delayed house exchange, spending three idyllic

weeks in lovely Wallingford – getting hitched at Didcot Registry Office on 20

September 2000. We kept everything quiet, having just Meg’s mother and brother

Glyn as the necessary witnesses. Jackie was not best pleased, but she understood

the reasoning.

Meg & I were

not married, even though Jackie and I were now divorced – we did not really

see any need for any formalisation of our love, but the threat of my dying caused

a re-think, purely to ensure that she would receive a UK state pension as my

widow. So, we decided to formalise our relationship and where better than back

in the UK. We picked up on the delayed house exchange, spending three idyllic

weeks in lovely Wallingford – getting hitched at Didcot Registry Office on 20

September 2000. We kept everything quiet, having just Meg’s mother and brother

Glyn as the necessary witnesses. Jackie was not best pleased, but she understood

the reasoning.