The training

programme

John Kidd was a student

of the Morgan Academy

in Dundee, where he obtained his higher education certificate. He volunteered

to join the RAF to fulfill his national service commitment, and signed on for

the extra years so that he could be trained as a pilot. As with many young men

the appeal of flying was a great attraction, even more so when he had experienced

the activity, and his intention was to try to remain in the service as a pilot,

even after his national service duty had ended. His induction took place in

January 1951 and this entry process was completed in RAF establishments at Padgate,

Driffield and Kirton in Lindsey.

In August he started his

flying training with No 1 Basic Flying Training School at RAF Booker, where

on August 24th, he made his first flight in a Chipmunk trainer. On the 17th

of September he made his first solo flight and by the time that he had completed

this course in late November, he had logged 62 hours of flying

The next stage of John's

flying training course was back in Scotland with No 8 Advanced Flying School

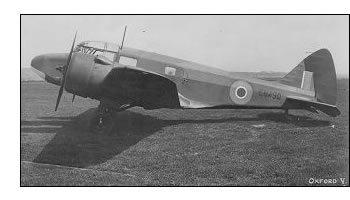

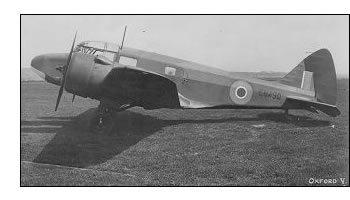

at RAF Dalcross. It was at 8 AFS that he began to learn to fly the Airspeed

Oxford twin  engined

aircraft. This aircraft had its origins dating back to the 1930's and it had

proved to be a useful crew trainer for the RAF who had a requirement for training

bomber crews during the 2nd world war. Large numbers had been produced and were

thus still available for pilot training in 1952. John was destined for service

as a fighter pilot, flying the RAFs front line fighter, the Meteor; but apart

from a twin engine configuration, the two aircraft had little in common, and

it was not the usual fighter training aircraft used by the majority of the flying

training schools. When this training programme is set against a modern one where

training aircraft have handling characteristics that are designed to be similar

to those of front line high performance fighters, its adoption looks distinctly

dangerous, as indeed it so often proved to be, with large numbers of the next

stage aircraft crashing, and their pilots being killed. However, as is illustrated

below, the need for pilots that were then urgently required seemed to warrant

less than perfect methods of training them.

engined

aircraft. This aircraft had its origins dating back to the 1930's and it had

proved to be a useful crew trainer for the RAF who had a requirement for training

bomber crews during the 2nd world war. Large numbers had been produced and were

thus still available for pilot training in 1952. John was destined for service

as a fighter pilot, flying the RAFs front line fighter, the Meteor; but apart

from a twin engine configuration, the two aircraft had little in common, and

it was not the usual fighter training aircraft used by the majority of the flying

training schools. When this training programme is set against a modern one where

training aircraft have handling characteristics that are designed to be similar

to those of front line high performance fighters, its adoption looks distinctly

dangerous, as indeed it so often proved to be, with large numbers of the next

stage aircraft crashing, and their pilots being killed. However, as is illustrated

below, the need for pilots that were then urgently required seemed to warrant

less than perfect methods of training them.

At this stage I feel that

the reader should be made aware of other relevant factors that may have influenced

the pilot training programme of early 1952.

In 1952, the Cold War was becoming well established; the era of Stalin had not

yet drawn to an end, the Berlin airlift was still fresh within people's memories,

and the Korean War had broken out. The reduction in the strength of the RAF

ended, and a boost was given to the recruitment and training of pilots. Conscription

was still in force and numbers of potential pilots were forthcoming. At the

start of 1950's the RAF was operating just one Meteor Advanced Flying School

(AFS), but by the end of the 1952, this number had increased to 10. The resulting

accident rate increased in proportion. Today's pilots train in dual controlled

aircraft, the fighter training types, even at the preliminary stages, have been

designed to display very similar handling characteristics to modern high performance

jets.

The current professional programme seems to have learned from the mistakes that

were made in the past, and accidents are thankfully quite rare.

Johns first

flight in the Oxford was made on the 6th December 1951 and by the end of May

of the following year he had completed the course, his flying log showing an

accumulation of 203 hours of service flying. He was awarded his wings on 30th

May 1952.

The pilot's

log book records a rather ominous insert, dated on the previous day the 29th

May. John had received an average rating from his instructor for both his piloting

and for his navigation skills A footnote has been added and I quote "Kidd

completely failed his first attempt at IRT. His reactions need to be speeded

up"

The IRT is

a test of his skill of flying the aeroplane on instruments, as would be experienced

in cloud conditions. Though these conditions would be simulated for the purpose

of the test, for the actual flying in cloud was a demanding activity for a student

pilot.

We must assume

that the test was completed successfully during a later attempt that day.

The next training

stage, that on jets, meant a move to Doncaster in South Yorkshire, where he

joined 215 AFS at RAF Finningley at the start of June 1952.

It was as

a member of course number 8, D flight 2 squadron, that he would learn to fly

the Meteor twin engined jet fighter.  His

first flight was in a Meteor T7 on June 13th and he began a series of

familiarization exercises that would enable him to fly solo. These having been

completed he began to fly the more numerous single seat Meteor Mk4, that were

in use at the Advanced Flying School.

His

first flight was in a Meteor T7 on June 13th and he began a series of

familiarization exercises that would enable him to fly solo. These having been

completed he began to fly the more numerous single seat Meteor Mk4, that were

in use at the Advanced Flying School.

These Mk4 aircraft were once front line fighters, but had been

relegated to the training role as the later Mk8 aircraft were brought into service.

The Mk 4, unlike the Mk8, did not have an ejection seat fitted.

As the course progressed John had reached exercises numbered 30

onwards. Exercise 30 being a cross country solo flight to RAF Oakington, just

outside Cambridge, and the return flight to base. This was done on 29th July

using the aircraft in which he was to loose his life a few days later. On that

same day he undertook Ex 31, which I believe was an instrument flying exercise.

This time he was flying in a T7 with Fl-Lt. Liskutin. On the Wednesday Thursday

and Friday, 30th July to 1st August, he had five more flights in a T7 aircraft

again with his instructor. These seemed once more to be instrument flying exercises.

Two were timed at 40 minutes each and three at 45 minutes. I assume that these

were carried out showing sufficient proficiency on the part of the student.

At the current state of this report I am not aware of the detailed timings nor

of the skills evaluated for the completion of Ex 31.

The pilot's log book shows no flights for the following week,

and it seems that he had gone home to Dundee for a week of leave. This absence

from flying training part way through this intensive, timed course is apparently

extremely unusual, and I cannot find a satisfactory explanation for it.

John returned from Dundee to Doncaster on the Sunday evening of 10th August.

He travelled by rail and was seen off at Dundee's Tay Bridge station, by his

sister Sheila. Sheila can recall that it was dark when the train left, so it

can be assumed that the pilot would not have arrived back on base until the

early hours of Monday morning. That same morning as he began his briefing for

his final flight, he may well have been tired from his long journey of the night

before.

To

the left is a photograph of what could be D flight, course number 8, the group

of pilots are standing in front of a Meteor.

To

the left is a photograph of what could be D flight, course number 8, the group

of pilots are standing in front of a Meteor.

PO J.S.Kidd is on the rear row, third from the right.

On the front row right, the pilot is wearing a uniform that does

not show a badge with RAF insignia, under high magnification, the beret badge

looks to be Czech, complete with red star! This pilot is probably the course

instuctor, Fl Lt. M.

A. Liskutin. He was the pilot of the T7 and formation leader on the day

of the crash.

At the time of writing none of the other pilots are known, apart

from Johns friend Peter (surname not known) who is on rear row second from right.

A

closer examination of the accident

engined

aircraft. This aircraft had its origins dating back to the 1930's and it had

proved to be a useful crew trainer for the RAF who had a requirement for training

bomber crews during the 2nd world war. Large numbers had been produced and were

thus still available for pilot training in 1952. John was destined for service

as a fighter pilot, flying the RAFs front line fighter, the Meteor; but apart

from a twin engine configuration, the two aircraft had little in common, and

it was not the usual fighter training aircraft used by the majority of the flying

training schools. When this training programme is set against a modern one where

training aircraft have handling characteristics that are designed to be similar

to those of front line high performance fighters, its adoption looks distinctly

dangerous, as indeed it so often proved to be, with large numbers of the next

stage aircraft crashing, and their pilots being killed. However, as is illustrated

below, the need for pilots that were then urgently required seemed to warrant

less than perfect methods of training them.

engined

aircraft. This aircraft had its origins dating back to the 1930's and it had

proved to be a useful crew trainer for the RAF who had a requirement for training

bomber crews during the 2nd world war. Large numbers had been produced and were

thus still available for pilot training in 1952. John was destined for service

as a fighter pilot, flying the RAFs front line fighter, the Meteor; but apart

from a twin engine configuration, the two aircraft had little in common, and

it was not the usual fighter training aircraft used by the majority of the flying

training schools. When this training programme is set against a modern one where

training aircraft have handling characteristics that are designed to be similar

to those of front line high performance fighters, its adoption looks distinctly

dangerous, as indeed it so often proved to be, with large numbers of the next

stage aircraft crashing, and their pilots being killed. However, as is illustrated

below, the need for pilots that were then urgently required seemed to warrant

less than perfect methods of training them.

His

first flight was in a Meteor T7 on June 13th and he began a series of

familiarization exercises that would enable him to fly solo. These having been

completed he began to fly the more numerous single seat Meteor Mk4, that were

in use at the Advanced Flying School.

His

first flight was in a Meteor T7 on June 13th and he began a series of

familiarization exercises that would enable him to fly solo. These having been

completed he began to fly the more numerous single seat Meteor Mk4, that were

in use at the Advanced Flying School. To

the left is a photograph of what could be D flight, course number 8, the group

of pilots are standing in front of a Meteor.

To

the left is a photograph of what could be D flight, course number 8, the group

of pilots are standing in front of a Meteor.