| Our Friend's Eccentric | |

|

The Word Issue 84 February 2010 Page: 39 |

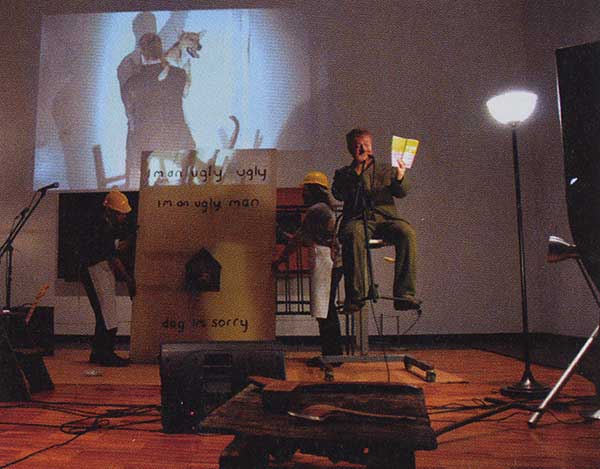

The ups and downs of Manchester's true outsider artist, Edward Barton THE HISTORY OF ALL THIS MUSIC begins with men singing about waking up this morning. Edward Barton sleeps a little later. "I woke up one afternoon and switched on the radio. I thought, 'That's a good tune, a very good tune. In fact that's my tune.'" The song was Kylie's 1994 international hit Confide In Me. Its main musical content had been taken from Barton's 1983 song It's A Fine Day, as covered by Opus III. Orbital nicked bits of it too, and so had some Italians, Norwegians and Israelis. The resultant money gave Barton the freedom - via his painting, his poetry and his own utterly personal music - to explore a darkly naive English eccentricity that makes Syd Barrett seem almost ordinary and Stevie Smith as fundamentally untroubled as Pam Ayers. You may not have heard of Edward Barton unless you saw him on The Tube in the mid-'80s, but Vic Reeves has. "When I think," the comic once said, "Ed Barton is what I think with." Barton's dedication to childlike experiments, be it in whole houses filled with wood or selfcurated club nights like Hip Replacement (where his dog chased about a raised false floor while a man underneath popped his toy-rabbit-clad arm up through holes) made Manchester laugh. But when everyone went home after a few happy hours in his disconnected world, Edward was left alone. "They incarcerated me in Withington mental hospital," he says. "It wasn't so much a breakdown as a break all around. I didn't speak to anyone for five years. I would only go out when it was dark". Now, a new album sees him once again communicating. He was, he says, so miserable that a friend gave him a computer just to keep him busy - to stop him from being sad. He had to show Barton which hand to put the mouse in. "It was like making a monkey do it. Hard. I took my time." But the result, the newly released album Edward Barton And A Panda, is wonderful. Edward Barton had signed to Cherry Red Records in 1982 with "about 15 songs" that, he naively thought, would turn the world around. Instead his live shows were generally greeted with thrown bottles. But in time the a cappellas business enabled him to buy a house in leafy Chorlton, giving up the five council houses he had acquired in Hulme, where he'd stored his collection of wood, shoes and teddy bears. "I had almost two houses filled completely with wood," he says. "The upstairs rooms were about to collapse. I like wood. Wood is flesh you can trust."  Barton grew up in Libya, the son of an RAF officer. When he first heard The Rolling Stones on the radio he remembers thinking it wasn't as good as "the waily, whirly stuff I'd heard in the bazaar". "When I was young, all I knew were camels and Biggles," he says. "Then they sent me to boarding school and the real world started to graze my eyeballs. I didn't want to break the rules, I just didn't recognise them. It never occurred to me that I couldn't do exactly as I wanted". In Manchester, where he settled in his mid-twenties, he quickly became uncrowned local royalty. You'd see him at the Hacienda all the time ("I loved house because I like funny noises in music, and that music had more funny noises per square inch than any other"). He made an acid record, Born In the North, with A Guy Called Gerald and started the Hip Replacement club, where his dog chased that toy rabbit and musicians played a joyously discordant racket from inside three large wardrobes. But the name of another club night, Misery, reflected Barton's growing mental state more closely. He slowly disappeared behind his big green front door into rooms ceiling-high with drawers full of stuff. "I didn't want to write songs at first, because songs made me sad. I wanted to make instrumental music - music that didn't talk back to me. Then one day I was walking up the stairs and I started to sing: `Like your shorts, boy'. By the time I got to the landing I had, 'Like your skirt, girl...'." More followed new songs as wonky, as tuneful and as treasurable as ever. "I seem to have this need to tell the world it's not enjoying itself the way I think it should be. I want to say, 'No, you're all doing it foolishly." One song is about blind men getting covered in custard in the queue for lunch at a charity drop-in centre. Let's see you tackle that, Kylie. [Author: JOHN McCREADY] |

|